![]()

Aroids and other genera in the Collection

Take the Tour Now?

Orchids

The

Exotic Rainforest

Images on this website are copyright protected.

Please contact us before

any reuse.

New:

Understanding, pronouncing and using

Botanical terminology, a Glossary

"Much of what we believe is

based on what we have yet to be taught. Listen to Mother Nature. Her advice

is best."

How should you care for your ZZ

plant? This easy to read article is based on the science of

this species, not internet rumors.

Can a pot containing the ZZ plant become

poisonous? Does Zamioculcas zamiifolia cause cancer?

Does this plant really need to be watered?

Should you believe all the internet rumors?

Zamioculcas zamiifolia

(Loddiges)Engl.

Zamioculcas zamiifolia

(Loddiges)Engl.

Z. "lancifolia"

and strangely

Caladium zamiaefolium (the basionym)

Aroid Palm, Arum Fern, ZZ Plant, Zee Zee plant, ZeZe plant, Zeezee Plant, Zu Zu Plant, Money Tree,

Fat Boy, Eternity Plant, Zanzibar Gem, Chinese New Year Festive Plant, Chinese Gold Coin Plant

and incorrectly "Succulent Philodendron", Emerald Fronds

Sometimes incorrectly spelled "Zamioculcus" using a second "u"

To water, or not to water?

If you find the advice on the internet difficult to believe or your specimen appears to be dieing anyway

read the article and you'll understand why the ZZ will go dormant if deprived of water!

The basis for the information

on this page can be

found in the scientific text

The Genera of Araceae,

by botanists Dr. Simon Mayo, J. Bogner and P.C. Boyce

The majority of home

growers have been lead to believe this species should not be watered, or

watered infrequently.

If you are having problems with your plant this article will explain why.

The reasons will probably surprise you!

The origins of the species Zamioculcas zamiifolia

The ZZ plant, Zamioculcas zamiifolia is found in a region of Africa which has somewhat extreme growing conditions. An unusual aroid (member of the family Araceae) the ZZ grows naturally in eastern Africa primarily in the countries of Zanzibar and Tanzania but the plant is also found in other western African countries. Although it is true those countries have a dry period it is not a desert species. The dry season does not persist year round since there is also a very wet period of heavy rain. This species definitely will suffer in the cold.

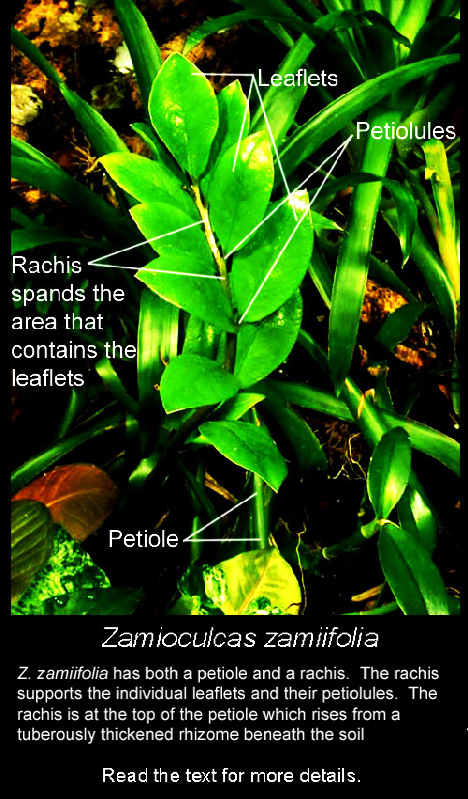

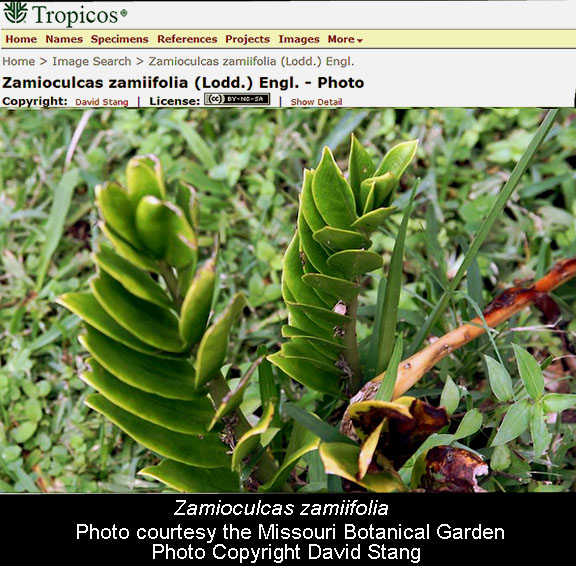

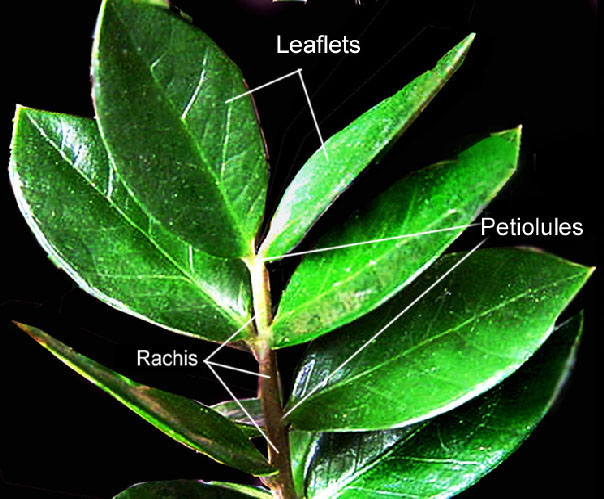

An aroid, Zamioculcas zamiifolia (ZAM-e-o-CUL-cas, ZAM-e-eye-FOL-e-a) is a sub-erect herb which sometimes grows to 0.75 meters (2.5 feet) or larger in height. It is commonly found growing in rocky areas as well as on stone in its native region of the African continent. Commonly known as the ZZ plant due to its unusual scientific name the plant is one of only a few species that can be regenerated from a single leaf blade (leaflet). The normal leaflet count is four to eight on each side of the rachis that is their , however in some variations the leaflet count can be substantially higher.

Common names and myths

Known by many regional as well as poorly devised common names including Zanzibar Gem, Aroid Palm, Money Tree, Eternity Plant, the Chinese New Year Festive Plant, Succulent Philodendron and Arum Fern the plant is popular around the globe Zamioculcas zamiifolia is neither a fern, a palm, nor Philodendron but it is in the same plant family as the genus Philodendron which is also a member of the plant family Araceae.

This species was described to science in 1905. Some sellers advertise Zamioculcas zamiifolia is a "new plant" but in truth Zamioculcas zamiifolia has been around since the beginning of time. Commercially, the plant has been sold since the year 2000. The genus name Zamioculcas was derived due to a vague similarity to the foliage of a group of Cycads found in the genus Zamia. The genus Zamia is in the family Zamiaceae which contains fern-like plants native to tropical and subtropical America while the ZZ plant is in a different family, ie Araceae. Despite the general appearance there is no scientific relationship between Zamioculcas zamiifolia and plants in the genus Zamia. The plant is also not a fern.

is the ZZ a desert plant?

Like much of the misleading plant information found on the internet it is commonly believed the ZZ plant is found in the desert. That information is absolutely false since the Royal Botanic Garden Kew in London states the plant grows in "tropical moist forest, savannas; geophytes on forest floor or in stony ground." See all the references at the bottom of this page. Aroid scientific texts state clearly there is only one aroid species found in desert terrain anywhere in the world, and it is not Zamioculcas zamiifolia. That information can be confirmed in the text The Genera of Araceae on page 46, "No Araceae occur in true deserts except Eminium spiculatum subsp. negeuense, from the Negev desert (Koach 1988)." Later in the same paragraph you can read, "Zamioculcas zamiifolia is a succulent plant which stores water in its thick petioles and is sometimes found in very dry habitats, but is more common in evergreen seasonal forests and savannas." The Negev is both a desert and semi-desert found in southern Israel.

The same misleading information attempts to tell you this plant does not need to be watered regularly which is completely in conflict with the normal growth information known by science regarding the species. I recently tried repeatedly to explain this to a plant forum discussion group interested in learning why some of their plants were dropping leaflets, a natural part of a compound leaf, but every single member appeared to refuse to accept any of the science or scientific reasoning why those leaflets were falling from the plant. Just like far too many growers, some prefer rumors to scientiic fact. There is a scientific cause for the leaflets to fall which is explained in this article and it has to do with the lack of water,

Scientific facts and a very false claim

The Genera of Araceae continues by stating the distribution of the single known species of Zamioculcas is tropical east and subtropical southeast Africa including Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa (Natal), Tanzania including Pemba , Zanzibar, and Zimbabwe. It further states the ecology of the plant is "tropical moist forest, savannas; geophytes on forest floor or in stony ground, forest floor or in stony ground". Please note this scientific text clearly states the plant is found in "tropical east and subtropical southeast Africa" as well as "tropical moist forest" along with other locations. Does that not make anyone wonder why the plant is commonly sold as an arid dry species that does not need water? If you have ever read about or visited a tropical or subtropical forest you already know it rains!

An invalid claim that appears to have originated out of SE Asia in the summer of 2010 now claims Zamioculcas zamiifolia can cause cancer! Internet discussion groups include the bogus notion the ZZ plant is so poisonous a clay pot cannot be used for another plant once it holds the ZZ since the "pot can be dangerous to touch". Such rumors are based on reading untrue information on another website and then, as happens with all rumors, enhancing and elaborating on it repeatedly, and posting an enhanced notion on another website again and again. These stories have been spread for years on the internet about aroids but no scientific foundation can be found. This quote came from retired research chemist and aroid expert Ted Held, "Just a quick check on Google ("Zamioculcas" and "poison") did not find anything substantive. As far as I can tell, this appears to be hysteria." Noted aroid botanist Peter Boyce in Malaysia responded, "The best one circulating here in Malaysia is that the pollen alone is enough to cause death in adult humans. I know of NO science whatsoever to back-up these claims."

If you believe the plant is dangerous because it contains calcium oxalate crystals you should know that the same chemical substance is found in Parsley, Chives, Cassava, Spinach, Beet leaves, Carrot, Radish, Collards, Bean, Brussels sprouts, Garlic, Lettuce, Watercress, Sweet potato, Turnip, Broccoli, Celery, Eggplant, Cauliflower, Asparagus, Cabbage, Tomato, Pea, Turnip greens, Potato, Onion, Okra, Pepper, Squash, Cucumbers, Corn and other vegetables most of us eat on a daily basis. It is true some aroids can be very distasteful and may even cause severe pain in the mouth and throat but to claim they are "deadly poisonous" is without merit. Just because something may taste really bad does not mean it will kill you. The best possible advice is to simply not put an aroid leaf in your mouth but I assure you aroids are eaten all over the world. Have you ever been to Hawaii and had Poi? How about Jamaica, the Caribbean or South America and dined on Callaloo, Taro, Dasheen, Dalo, Eddo or Potato of the Tropics? All are Colocasia esculenta, a common aroid developed by the Chinese more than 10,000 years ago as a staple diet. People eat it all over SE Asia every day! (click the link to read more) If you are prone to believe falsely elaborated internet rumors please read this link which provides information based in science: Calcium oxalate crystals

If to this point you are finding some of the words we must use difficult to comprehend we attempt to explain all of them as simply as possible at this link:

New: Understanding, pronouncing and using Botanical terminology, a Glossary

How

Zamioculcas zamiifolia grows in

nature

Zamioculcas

zamiifolia is found naturally growing in lowland forests on rocky

lightly shaded terrain (infrequently in deep shade) as well as dry

grassland. The species appears to enjoy moderately bright light and

more than one scientific observer has seen them growing in direct sunlight!

This species commonly becomes deciduous during dormancy! Becoming deciduous is the

natural dropping of the leaves during the dry season. If you found

this site because your plant has begun to drop leaflets the reason is

natural. Your plant is going dormant, likely due to insufficient water.

Once the

leaflets begin to drop it is not uncommon for them to form a bulblet or

tubercle at the point where the

rachis and petiolule supporting the leaflet join. The

petioles that support the rachis are green with darker blotches

that run transversally across the petiole. These leaflet tubercles

allow the regeneration of a new plant. The tubercles regularly develop

at the juncture of the rachis and petiolule.

Despite

incorrect

information found on the internet this species does not grow from a

bulb or a corm. Although there is an ongoing discussion among aroid

botanists about the possibility of some plants related to the

Amorphophallus group growing from a "corm-like" unit, technically all aroids that have an underground starch storage until

only grow

from a tuber with some growing from tuberous roots. Despite claims on some garden websites,

Zamioculcas zamiifolia

is not stem-less. Instead, the ZZ or Zee Zee grows from a specialized

form of

stem known as a tuberous rhizome. This underground tuber form, a crown with tuberous roots, is the stem.

from a tuber with some growing from tuberous roots. Despite claims on some garden websites,

Zamioculcas zamiifolia

is not stem-less. Instead, the ZZ or Zee Zee grows from a specialized

form of

stem known as a tuberous rhizome. This underground tuber form, a crown with tuberous roots, is the stem.

Since the plant can tolerate long periods without water the internet is filled with half truths about this species that are not scientifically accurate. Yes, it will survive, but that does not mean it will be comfortable. Despite the information often offered, the plant needs water like any other plant and is more inclined to drop all the leaves if not watered! During the native dry season Zamioculcas zamiifolia does become totally deciduous and commonly sheds all its leaflets while it waits for the rainy season to return. Those leaflets are then capable of regenerating a new plant as a result of the tubercles that can form on their petiolules.

The scientific text, The Genera of Araceae states this type of leaflet to plant regeneration is not common under the heading Leaf tubercles and regeneration: "Tubercles regularly develop at the juncture of leaflet and petiole in Pinellia ternata (Hansen 1881, Linsbauer 1934, Troll 1939), at the apical end of petiole in Typhonium bulbiferum (Sriboonma et al, 1994) and at the first and second order divisions of the leaf of Amorphophallus bulbifer (Troll 1939)- Tubercles in Pinellia may also form spontaneously along the petiole or can be induced in the basal part by cutting into segments (Linsbauer 1934). Tubercles may develop in Typhonium violifolium at the leaf apex, the petiole apex and at the apex of the sheath (Sriboonma et al, 1994)."

"Regeneration of tubers, leaves and roots from leaf segments is well known in Zamioculcas zamiifolia and Gonotapus boivinii (Engler 1881, Schubert 1913, Cutter 1962). Isolated entire leaflets of Zamioculcas and Gonatopus spontaneously develop a basal swelling, followed by the formation of roots and up to 3 buds, over a 6-9 week period for Zamioculcas. Leaf regeneration in Gonatopus is more rapid. The results of experimental manipulation of isolated leaflets grown in culture show that any part of the compound leaf is capable of regeneration".

Compound leaves, leaflets and a unique form of stem: a thickened Tuberous Rhizome

I

In the case of plants with pinnately compound leaves, such as Zamioculcas, the arrangement f the separate leaflets is like the structure of a feather. The portions of the leaf stalk where the leaflets are joined along a common axis is known as the rachis (RAY-kis), Below this point the stalk is called the petiole and it is in turn attached to the stem. Thus, rachis and petiole are terms used to differentiate parts of the same structure which is composed of a number of leaflets. While a palmately compound leaf blade consists of leaflets radiating from a single point at the distal end of the petiole and have some some resemblance to that of a hand, in either case the individual leaflets may be sessile (not possessing a stalk) or supported by short stalks called petiolules. Distal refers to region of an organ that is furthest away from the organ's point of attachment. See the photo at the top of this page to understand the position of all these plant parts.Despite incorrect descriptions on well-meaning well sites, the petiole grows from a central axis structure at or just below the surface of the soil known as a rhizome. While one well known site states the plant can live for long periods without water "due to the large potato-like rhizome that stores water until rainfall resume", in the case of Zamioculcas the rhizome is somewhat tuberous or tuberously thickened, but is neither large or potato-like. The rhizome does however correctly exist for the purpose of water and food storage during the dry season. The next time you repot your plant look at this organ carefully and it will become obvious many sites describe it inaccurately.

Although "tubers" are potato-like starch storage units, the tuberous rhizome of this species is highly specialized, different in shape and is somewhat difficult to accurately describe to those not experienced in aroid botany. In the original work (see below) it is described as being sub-cylindric

but In this case the rhizome resembles a crown and serves the purpose of a tuber, thus the stem. It also possesses the buds for new growth.If you are familiar with the term "tuberous roots", that term should not be confused with the tuberous rhizome of Zamioculcas zamiifolia. Tuberous roots are true root tissue that is swollen possessing tuberous portions that radiate from a central flattened rhizome known as a crown. The tuberous roots do not have buds but appear and act somewhat like tubers without being a true tuber or stem. Each root has a portion of stem tissue attached but they are nutrient-storing root tissue with thickened fleshy parts. The tuberous roots typically grow in a cluster and may also put out fibrous roots to take up moisture and nutrients . Tuberous rhizome root systems often permit the plant to survive difficult annual growing seasons that may kill the portion of the plant above the soil. Although growers that are familiar with plants such as a Philodendron often try to call the petiole a "stem", in the case of this species the true stem (crown) is underground.

Tuberous

roots do not have buds but appear and act somewhat like tubers without

precisely being

a true tuber. Each root has a portion of stem tissue attached but

they are nutrient-storing root tissue with thickened fleshy parts. The

tuberous roots typically grow in a cluster and may also put out fibrous

roots to take up moisture and nutrients . Tuberous root systems

often permit the plant to survive difficult annual growing seasons that may

kill the portion of the plant above the soil. Although growers that are

familiar with plants such as a Philodendron often try to call the

petiole a "stem", in the case of this species the true stem (crown) is

underground

The subject of tubers versus

rhizomes and tuberous roots is often quite complicated and not every

definition on the subject is set in stone. Many botanical references do not

define these terms or qualify them clearly and the plants themselves do not

always abide by our predefined definitions. The information presented

here is done solely to make an effort to explain the subject as simply as is

possible for the average grower. The petioles are the stalks that support

the rachis and thus each leaflet and the petioles should not be called

"stems".

This link explains the difference between a stem and a petiole, bulbs, corms, tubers and rhizomes.

Self duplication from nothing more than a fallen leaflet

When the leaflets fall to the ground they attempt to replicate themselves as a natural reproductive process by growing a small tuberous rhizome which forms naturally at the junction of the rachis and the leaflet but roots may develop from other parts of the leaflet. Once the rainy season arrives the habitat is no longer dry and the plant has managed to survive by duplicating itself but can grow very well in a wetter growing situation. Plants that have survived by appearing to be "dead" can then grow new leaflets.

The stem (central axis) of the plant is found underground as a crown described as a tuberous rhizome. The tuber is correctly known as the stem which supports the petiole that supports the petiolules and leaflets. The petiole, rachis and petiolules are technically a part of a leaf or leaflet and during the wet season both the stem and petiole swell to store water as do other succulents. Being able to survive without water is a survival characteristic, not a normal growing condition, so the ability to store water in a water retention structure is vital to the long term survival of this species.

Since tubercles can be regenerated at the junction of the leaflet and rachis this is one method from which a new plant can be naturally propagated by a home grower. This characteristic is limited in the family Araceae (aroids) to Zamioculcas zamiifolia and Gonotopus bovinnii. A very few other species can be grown from a leaf cutting including some Amorphophallus species as well as one known aquatic aroid.

Using this unique survival ability house

plant growers may be able to grow their own plant using this unique

characteristics by placing a leaflet with a petiolule in a a closeable clear

salad container with a sandy soil mix also containing a small amount of good

soil, Perlite, and bark. With the

adaxial surface (upper side) facing upwards. Keep the high humidity in

the container by covering the leaflets with the lid or clear plastic kept in moderately bright light.

You may just be lucky enough to grow a new plant but be aware the

process is not rapid easily taking months!

The origins of the bad information on the internet.

Since I am aware that some "self declared experts" on a variety of websites believe the information on this page is untrue I have elected to reprint portions of the text from the scientific text The Genera of Araceae within the article. Please recall that since the original information was written it has been scientifically determined there is only a single species in the genus Zamioculcas. You can decide for yourself if gardening advice should take precedence over scientific evidence. Near the bottom of the page is the major scientific evidence regarding this species from the ultimate authority on plants, the Royal Botanic Garden Kew in London.

Many websites simply pass along growing ideas promoted by plant sellers which sometimes work to the benefit of the seller, not the house plant grower. Even though many sites incorrectly recommend to rarely water the plant if you read a scientific text written by a botanical expert you will learn the ZZ plant lives in a long period of wet followed by enduring the normal dry season. Just because a plant can endure a drought does not indicate it prefers a drought. Recommending to rarely or never water a specimen is very poor advice since the plant needs both a wet season along with a somewhat drier period. Leaving the plant constantly dry will only result in the eventual loss of the leaflets and likely the plant if it is not quickly resuscitated with water.

If you check garden websites you will read where house plant growers commonly ask why their ZZ plant is "dying" and loosing all the leaves when they are "following the rules". Those are the same "rules" which advise growers to rarely water the plant. Quite simply, those "rules" are not correct! Because some growers don't understand what the term deciduous means house plant growers tend to panic and think their plant is about to die. Had the plant been watered regularly there is often no reason for the deciduous period to even begin.

It would at least appear some sellers prefer not to tell customers to expect the plant to drop its leaflets if kept dry since you are more likely to just buy a new plant. In truth the condition is a natural part of the plant's growth and reproductive cycle. The loss of all the leaflets does not indicate a plant is almost dead but simply suffering as a result of a genetic survival ability and poor growing growing conditions. If you starve a plant for water the plant is going to do exactly what Nature designed it to do and go into its survival mode. Without the water to work with the chlorophyll to produce sugars the plant has no source of natural food.

Some sites including eHow also give very poor advice on how to grow the plant including recommending the use of "rich soil". Even though a specimen can survive for an amazingly long period of time in rich soil that holds water that does not mean the plant enjoys the condition in which it is being forced to survive. The information to use rich soil is not based in science since the plant grows naturally in fast draining sandy soil.

Proper soil mixtures and why rich soil can kill your plant

Rich soil eventually suffocates as well as "drowns" a specimen causing the tuberous roots to rot due to the growth of saprophytes. A saprophyte is an organism such as a fungus or bacterium that grows on and derives nourishment from dead or decaying organic matter. When the roots of Zamioculcas zamiifolia are kept in wet soil they cannot easily gather oxygen and thus begin to decay. The end result is rapidly rotting roots and eventually a dead plant.

Following Mother Nature's example the soil mixture should be close to that used for cacti and should contain some soil along with a greater volume of sand, gravel and materials including Perlite that will slowly allow the roots to gather moisture while not being starved for oxygen. The plant should be regularly watered but not allowed to stay wet! In nature the ZZ can survive for long periods only as a naked petiole but as a house plant it certainly won't be attractive without the leaflets. Just as a human or animal can uncomfortably survive for periods of time with no food and water so can the ZZ plant. Even though nature has designed the species to survive with little water that does not mean it should be purposely dehydrated! The assumption the ZZ plant should be kept dry year round is a total internet myth and house plant seller's fabrication.

It appears sellers are actually promoting this plant as a house plant because they claim you can forget to water it for long periods of time. For short periods perhaps, but not indefinitely! The plant may survive but it will also not prosper and in time will look quite bad just as your cat or dog would look terrible if not fed and watered. It is likely a very large number of plants are thrown away every year once all the leaflets drop because the grower incorrectly believes it is dead. In most cases, unless the plant has endured a very long spell without water, it can be easily saved with time and water!

This message came from aroid botanist Peter Boyce who is one of the authors of The Genera of Araceae published by the Royal Botanic Garden Kew in London. Pete lives and works in Malaysia, "It is a very popular plant, especially with the Chinese, who regard it as lucky (i.e., bringing in money) by the way it can regenerate by the leaflets. Here we grow it either in pots of red soil (mainly derived from local ultisols of pH 4-5) mixed with 1/5 bulk coarse sand to give a water permeable mix that is high in nutrients, or in the open ground in medium shade. In both 'habitats' plants will receive water virtually every day either from rainfall (Kuching receives ca. 5 m per annum) or in times of no rain then from hand watering. In such conditions plants grow very quickly, producing a new leaf every 3 - 4 weeks. A plant raised from a single leaflet will carry 12 - 15 leaves and ca. 75 cm tall within a year. The one caveat to giving so much water is that our temperatures are permanently high; minimum 22 C nighttime and 28 C daytime with maxima of 26 C and 36 C respectively. Humidity averages 80%." Since Pete was quoting temperatures in Celsius it should be noted those temps would be the equivalent of very warm in the United States.

Despite what you've read, the ZZ is not a Philodendron, a palm nor an orchid

Despite information on a few websites this species is not a Philodendron. The genus Philodendron is found only in the Neotropics which include the Caribbean, southern Mexico, as well as Central and South America. Although Philodendron are grown by individuals all over the world, they are naturally found only in the Neotropics and not in Africa or Asia. The only relationship between the genus Philodendron (over 1000 species) and the genus Zamioculcas (containing one species) is both genera are aroids. The common name "succulent Philodendron" is a very poor choice for a common name!

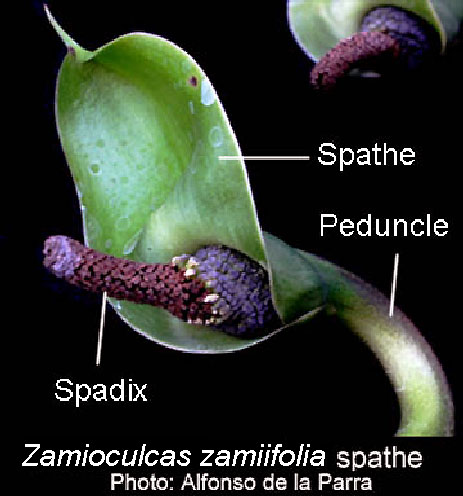

Zamioculcas zamiifolia is also not an orchid nor a palm even though at least one website is saying the species is an orchid! Orchid species produce very distinctive flowers which always contain three petals and three sepals. Zamioculcas zamiifolia does not produce a "flower". Instead the ZZ produces an inflorescence with a spathe and spadix. There are very tiny flowers on the spadix when it is ready to be pollinated, but you would need a magnifying glass to see them. All the synonym names listed above are now considered to be the same species: Zamioculcas zamiifolia. They differ only due to natural variation. Variation is explained later in this article.

Most Zamioculcas zamiifolia are mass produced for sale. The majority of specimens sold in discount nurseries are not grown from seed but instead created in a laboratory by a chemical process known as tissue culture (TC or cloning). The genetic material was extracted from an adult plant, replicated in a laboratory and grown in a lab dish. Once the plants begin to form they are then grown in multi-chambered trays before being sold to a commercial grower who transfers each plant to an individual pot.

This strange plant has been reported on some websites to reach a maximum height of approximately 50cm or 20 inches, but Zamioculcas zamiifolia can grow much larger. The debate is a result of a discovery by aroid botanists who have recently been required through scientific study to combine all the synonyms (other names for the same species) into the single species of Zamioculcas zamiifolia. Interestingly the basionym for the species is Caladium zamiaefolium even though the only relationship between the genus Zamioculcas and the genus Caladium is both are aroids. A basionym is the original name applied to the taxon (species). The word is composed of "basio" from the Latin meaning basis, from the Greek "bainein" meaning step, and "nym" also from the Latin word "nomen" which means name. A basionym is the first step in the naming process. The confusion arose many years ago when botanists had yet to clearly define all the species in the family Araceae and simply had no idea which genus properly fit the strange plant. At one time the species names including Zamioculcas loddigesii, Zamiacaulcas zamiifolia and Zamioculcas lanceolata were considered to be unique species but all are now considered to be the single species Zamioculcas zamiifolia. The difference in all the names appears to have been only the size of the plant or other non-significant differences due to natural variation.

The Natural variation in aroids

Within aroids variation in leaf shape, plant size and other characteristics is common. As a result many aroid species have multiple characteristics which serve to confuse novice collectors. The final determination of the species is found within the of the inflorescence of the plant which contains the sexual parts. If those sexual parts are the same from plant to plant then they are the same species. Consider natural variation to be like human beings. We have many different faces, hair color, skin color and body sizes but is only a single species of human beings.

Even though you will later read in this article a reference to "other species", noted and frequently published aroid expert Julius Boos pointed out in a post on the aroid discussion forum Aroid l (L), "The genus East African Zamioculcas, as presently understood, consists of just one widespread but variable species, Zamioculcas zamiifolia (Loddiges) Engler. This may be confirmed by reading the two most recent works on the genus, Pg. 149 of "The Genera of Araceae" by S.J. Mayo, J. Bogner, and P.C. Boyce, and a recent update in "Aroideana", Vol 28, 2005, pg. 3, by Josef Bogner. You may note that in the article in Aroideana, figs. 4-6, pg. 7, Josef notes that Z. "lancifolia" is a synonym of Z. zamioculcas." Aroideana is the annual publication of the International Aroid Society.

Aroids are a fairly large group of approximately 3800 species of plants that reproduce by the production of an inflorescence (see photo below of the spathe and spadix of Zamioculcas zamiifolia). You have likely seen an aroid inflorescence if you have ever grown a Peace Lily (Spathiphyllum). If pollinated by an appropriate insect, brown berries will develop on the spadix and those berries are ellipsoid in shape and will produce seeds. The berries grow on the sides of the upright spadix at the center of the spathe and the pair is known as an inflorescence. On any aroid that spathe is not a flower but is instead simply a modified leaf. The ZZ plant normally produces one to two inflorescences during its natural reproductive period.

Sexual reproduction

Little is

known by science as to the sexual reproduction of this aroid species.

However, it is easily reproduced from a single leaf. Julius explains,

"I believe that there

may not be photos of fruit developing on this most interesting African aroid

Zamioculcas zamiifolia because it is so easy to reproduce by just sticking a

leaflet in the soil as is its close relative Gonotopus! Zamioculcas belongs

to the group of aroids which produce unisexual blooms. In other words

they produce spadices consisting of separate zones. The female zone is

at the base with the male zone and sometimes with one or rarely a couple

of sterile zones arranged above the female zone. From illustrations of the

spadix of this genus it would appear that there is a vary narrow sterile

zone between the female and male zones. It should be a fairly simple matter

for an owner of one of these plants at maturity (and

with several blooms

developing/opening), to select the most mature bloom when it is at male

anthesis after the bloom has opened

fully and is visibly producing pollen

and to collect pollen on a small brush wetted with distilled water and

transfer this

pollen to the female zone of another younger bloom just as it

is beginning to open. One may have to carefully cut away a bit of

the spathe

to get at the female zone. It may take a few attempts to get the timing

right as I speak in general terms here. I have always been interested in

the pollinators and strategy for pollination which Zamioculcas seems to

employ. The blooms are produced on short peduncles almost at ground

level. As they mature they lean over on the peduncle and as they open

the spathe sort of unrolls toward ground level, seemingly to provide a ramp

or ''red carpet'' to facilitate visiting insects walking on the ground,

perhaps ants or terrestrial beetles in its home range! If one is successful

in pollination and fruit/seed production, it will be most interesting to

learn what strategy is employed by this plant for dispersal of its fruit and

seed, based on the size and texture of its fruit and seeds, to speculate

what insects or birds or mammals might be the distributors!"

A peduncle is the

stalk-like support for an inflorescence and is the

internode between the spathe and

the last foliage leaf.

zone between the female and male zones. It should be a fairly simple matter

for an owner of one of these plants at maturity (and

with several blooms

developing/opening), to select the most mature bloom when it is at male

anthesis after the bloom has opened

fully and is visibly producing pollen

and to collect pollen on a small brush wetted with distilled water and

transfer this

pollen to the female zone of another younger bloom just as it

is beginning to open. One may have to carefully cut away a bit of

the spathe

to get at the female zone. It may take a few attempts to get the timing

right as I speak in general terms here. I have always been interested in

the pollinators and strategy for pollination which Zamioculcas seems to

employ. The blooms are produced on short peduncles almost at ground

level. As they mature they lean over on the peduncle and as they open

the spathe sort of unrolls toward ground level, seemingly to provide a ramp

or ''red carpet'' to facilitate visiting insects walking on the ground,

perhaps ants or terrestrial beetles in its home range! If one is successful

in pollination and fruit/seed production, it will be most interesting to

learn what strategy is employed by this plant for dispersal of its fruit and

seed, based on the size and texture of its fruit and seeds, to speculate

what insects or birds or mammals might be the distributors!"

A peduncle is the

stalk-like support for an inflorescence and is the

internode between the spathe and

the last foliage leaf.

Pollination of Zamioculcas zamiifolia is caused by a unique set of circumstances devised by nature. As with virtually all aroids and numerous other plant species a single insect pollinator species has been assigned the task of collecting pollen from a plant producing mature male flowers at male anthesis and then transports that pollen to the sexually mature female flowers of another plant during female anthesis. The female flowers which are receptive to pollen are separated from the male flowers which produce that pollen via a zone of sterile male flowers. The spadix is known to have a bi-sexual inflorescence containing the male, sterile male and female flowers in distinct zones. This technique is used to prevent self pollination but in some species that is still possible.

It is unknown for certain if this species is capable of self pollination and science is not currently aware of the exact insect species involved in the process. The male of that insect species is attracted to the mature female flowers which grow along the spadix by a unique pheromone or perfume. A single molecule of that pheromone can be detected at great distances by the olfactory senses of the male insect. Although not completely documented, to a male insect that pheromone may smell similar to the female of his own species who is ready to be impregnated. As the spathe reaches sexual maturity it reflexes once the small female flowers along the spadix are ready to be pollinated. Once ready, the peduncle which is always short and is the structure that supports the inflorescence curves in to move the inflorescence towards the ground to the point of contact. If pollinated the berries that contain the seeds will be white.

As explained by Julius, the goal of the plant

appears to be to reach the ground thus facilitating possible ground dwelling

pollinators such as an ant or beetle to climb into the tiny blooms in

to spread pollen from other specimens to the female flowers thus causing

pollination. For those scientifically inclined, the entire process is

explained in detail in the scientific text The Genera of Araceae

by botanists Dr. Simon Mayo, J. Bogner and P.C. Boyce on page 146 and

following. You should be aware this text is quite costly

and written using scientific terminology. If

you elect to read it bring along a botanical dictionary. If you are

interested in learning more about aroid pollination please find the link at

the bottom of this page which will lead you to a basic introduction into

aroid sexual reproduction.

The species is highly variable and there are specimens that

are substantially taller than the published "maximum" height on

some websites. Individual specimens attain a variety of

sizes largely due to

growing conditions. Zamioculcas zamiifolia grows with all its glossy leaflets facing

in one

direction, a structure known to botany as pinnate leaves. Pinnate

leaves are those arranged similar to the fronds of a palm. The plant's

structure is likely to have led to the common name "Aroid Palm".

This link offers a more complete explanation in non-technical language

regarding natural variation and morphogenesis within aroid species

Natural variation.

Potting your plant

Experienced growers who understand aroid species frequently recommend planting a specimen in well draining soil such as a moisture control mix with more than 50% sand and Perlite™ added. Most experts advise not to keep the roots of this species in mud and to avoid "off the shelf" potting soil mixes. If you have attempted to pot your plant in Miracle Grow or other soggy soil repot it now!

Differences of opinion

Since this species is an aroid, in the first week of August, 2007 one of the world's best known aroid botanists, Dr. Thomas B. Croat Ph.D., P.A. Schulze Curator of Botany of the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis, MO. asked a group of well qualified aroid growers, experts, researchers, some botanists and numerous professional aroid growers from all over the world this question via the discussion group Aroid l (L). Dr. Croat does not specialize in African species, "A colleague here at the Gardens asks what are the best soil conditions and general care for this species. We have it in the greenhouse where it thrives but do any of you grow it in your house. Does it require special care? I would appreciate it if anyone has any advise."

The answers to his question was varied and

may surprise you!

"The plant is nearly bullet proof. If you grow it in a house it will grow

very slowly. In a greenhouse it will grow like mad. Mine was 10 cm tall, in

a room with no natural light and rare waterings after a year it looked the

same. Moved to the greenhouse fed and watered it, and in a year it was more

than a meter tall."

"My daughter gave me one about two years ago. I read everything i could

find and according to what I can locate Zamioculcas zamiifolia enjoys drier

arid conditions. Supposedly, it likes water in the rainy season and little

moisture during the dry season. That just didn't fit into the way I grow

aroids in my tropical atrium, so I just planted it! In fact, it is just feet

away from my large Anthurium regale. The plant is watered as often as all

the other tropical aroids and does just fine! It is in very lose soil with

lots of sand added. But other than that, we don't do anything special. To be

honest, I wasn't crazy about the thing. But my daughter read it was an aroid

so she got it for me. It may eventually not survive, but for several years

it has tolerated my "tropical conditions" well."

"I agree with what (name removed) reported, both on what research will tell

you the plant wants, some moisture and then a dry season, and on what his

reality was, and mine as well. We planted ours in an upper planter pocket in

the rain forest simulation at UNC Charlotte, where it was fairly well

drained but pretty constant moisture as well, and it just thrived, flowered,

the whole nine yards. It got some sun, but not much - just good bright

light, well drained soil, and good moisture. It got real good sized for us

under those conditions."

"Keep it well drained. It can be grown in an orchid compost (tough or

graded bark mixed with an equiv volume of peat moss) or peat moss - perlite (5-0

mm) equiv mix or in sand (5-0 mm) - peat 3:1 mix. I got an over watered one

and I kept it dry for 2 months now it looks better."

Many of these folks are professionals and botanical experts, others simply

collectors. Just put it in sandy soil and do your thing! In fact, it seems the people who water it more may actually have

better results with better growth and a healthier plant! The key appears to be in having well draining

sandy soil. Obviously there is no single

path to the perfect growing of

Zamioculcas zamiifolia . Every grower needs to do their own

research and find what works best.

As for how much to water the answer appears to be water as much

as you like but if you want it to prosper more than you are likely

offering the plant right now, especially if your specimen is not

"growing like a weed"

.

Soggy soil, sandy soil that drains and oxygen

If your plant is in soggy potting soil get it out! If it is totally dry, Water it!

Despite what some self proclaimed "expert" may insist on a plant forum, all plants need water in order to combine with carbon dioxide in order for the chlorophyll inside the leaflets to produce carbohydrates in the form of sugars to feed the plant. As a part of this natural photosynthesis the sugars provide sustenance to the plant and the byproduct of oxygen is then returned to the atmosphere for other living organisms to breathe. Plants also draw in oxygen through the roots which is why it is imperative the soil the plant lives in be extremely porous (both loose and sand based). If you choose not to water the plant it has no choice other than to eventually go dormant in order to survive. If still left dry for long periods of time it will eventually cease to exist as a living organism. For some length of time it is likely to look beautiful but one day IT WILL GO DORMANT. Without photosynthesis which requires light and water no plant can life indefinitely since they will eventually starve to death and in order to preserve its own life as long as possible it will simply slip into dormancy and appear dead.

Advice from the scientists

Please be sure and read their explanation regarding where this plant grows in nature: "ECOLOGY: tropical moist forest, savannas; geophytes on forest floor or in stony ground." This species does not grow in a desert as is commonly advised. Instead, it grows in tropical moist forests as well as in savannas and on stony ground!

My thanks to Dylan Hannon, Curator, Conservatory and Tropical Collections at the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens for his assistance in explaining the tuberous rhizome root system. Additional thanks to Jonthan Ertlet for his additional clarifications.

The scientific treatment of

Zamioculcas zamiifolia:

From the Royal Botanic Garden Kew website, CATE Araceae

Tuber subcylindric, ± 3-4 cm. in diameter or more, tough, woody.

LEAVES: Petiole green

with darker transverse blotches, 15-35 cm. long, 1-2 cm. in diameter near

base; blade 20-40 cm. long; leaflets 4-8 per side, subopposite, distant,

oblong-ovate to -elliptic to -obovate, sometimes oblanceolate, fleshy, dark

glossy green, 5-15 cm. long, 1.5-5 cm. broad, shortly acuminate, sessile or

shortly petiolulate, articulated to rhachis, cuneate to rounded basally;

rhachis terete, marked like petiole. INFLORESCENCE: Peduncle 3-20 cm.

long, 0.4-1 cm. in diameter, erect at first recurving strongly in fruit,

pushing infructescence into ground-litter. Spathe 5-8 cm. long, coriaceous;

tube shortly cylindric to ellipsoid, 1-1.5 cm. long, 1-2 cm. in diameter,

green on outer surface; limb broadly oblong-ovate, 5-6 cm. long, 3.5-5.5 cm.

broad, rounded and cuspidate at tip, pale green to whitish or yellow. Spadix

5-7 cm. long; staminate part cylindric to clavate, 4-5 cm. long, 1-1.5 cm.

in diameter, narrowed at base; pistillate part shortly cylindric-ellipsoid,

1-2 cm. long, 0.7-1.7 cm. in diameter. Tepals white; stigmas yellowish.

INFRUCTESCENCE: Berry white, surrounded by persistent tepals, with

septal suture, up to 1.2 cm. broad, 1-2-seeded. Seeds brown, ellipsoid, ±

0.8 cm. long, 0.5 cm. broad. Zamioculcas Schott, Syn. Aroid. 71

(1856). TYPE: Z loddigesii Schott, nom. illeg. {Caladmm zamiaejbUum Loddiges,

Z. zamiifolia (Loddiges) Engler).

HABIT: seasonally dormant or evergreen herb with short, very thick rhizome.

LEAVES: few to many, erect, leaflets deciduous during dormancy leaving

persistent petiole. PETIOLE: terete, base greatly thickened and succulent,

geniculate at apex, sheath ligulate, free almost to the base, very short,

inconspicuous. BLADE: pinnatisect, leaflets oblong-elliptic, thickly

coriaceous, capable of rooting at base once shed and forming new plants;

primary lateral veins of each leaflet pinnate, running into marginal vein,

higher order venation reticulate. INFLORESCENCE: 1—2 in each floral

sympodium, held at ground level. PEDUNCLE: very short. SPATHE: entirely

persistent to fruiting stage, slightly constricted between tube and blade,

green without, whitish within, tube convolute, blade longer than tube,

expanded and horizontally reflexed at anthesis. SPADIX: sessile, female zone

subcylindric, separated from male zone by short constricted zone bearing

sterile flowers, male zone cylindric, ellipsoid to clavate, fertile to apex.

FLOWERS: unisexual, perigoniate; tepals 4, in two whorls, decussate. MALE

FLOWER: tepals subprismatic, apex thickened, stamens 4, free, shorter than

tepals, filaments free, oblong, thick, somewhat flattened, anthers introrse,

connective slender, thecae ovate-ellipsoid, dehiscing by apical slit,

pistillode clavate, equalling tepals. POLLEN: extruded in strands, extended

monosulcate to perhaps fully zonate, ellipsoid, large (mean 60 urn.), exine

thick, fossulate-foveolate, apertural exine verrucate. STERILE FLOWERS: each

consisting of 4 tepals surrounding a clavate pistillode. FEMALE FLOWER:

tepals strongly thickened apically, st ami nodes lacking, gynoe-cium

equalling tepals, ovary ovoid, 2-locular, ovules 1 per locule,

hemianatropous, funicle very short, placenta axile near base of septum,

stylar region attenuate, stigma large, disco id-capitate. BERRY:

depressed-globose with furrow at septum, 1—2-seeded, surrounded by

persistent tepals, white, infructescence ellipsoid. SEED: ellipsoid, test a

smooth, brown, raphe conspicuous, embryo large, rich in starch, endosperm

nearly absent, present only as a few cell layers at chalazal end.

CHROMOSOMES: 2n = 34.

DISTRIBUTION: 1 sp.; tropical east and subtropical southeast Africa:— Kenya,

Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa (Natal), Tanzania (incl. Pemba, Zanzibar),

Zimbabwe. ECOLOGY: tropical moist forest, savannas; geophytes on forest

floor or in stony ground.

Aroid Pollination!

As

it occurs in nature and by any horticulturist

Want to learn more

about aroids?

Join the

International Aroid Society:

http://www.exoticrainforest.com/Join%20IAS.html

Back To Aroids and other genera in the Collection