![]()

Aroids and other genera in the Collection

Take the Tour Now?

Orchids

The

Exotic Rainforest

The images on this website are copyright protected. Please contact us before any reuse.

"Much of what we believe is

based on what we have yet to be taught. Listen to Mother Nature. Her advice

is best."

New:

Understanding, pronouncing and using

Botanical terminology, a Glossary

Caring

for Spathiphyllum

Species and hybrids

Growing a "Peace Lily"

Compare what Mother Nature has chosen to do versus everything you've

been told!

Common names: Spath, Spathe, "Peace Lily", Snow Flower

Don't be afraid to water

your "Peace Lily". They grow naturally in water!

Just pot it correctly!

Looking for specific information? Please scroll down through the

topics discussed below

If you already doubt this plant

likes water since you have seen one appear to die from water please at least scroll

down and read the paragraphs on Fermentation and Saprophytes. That was

likely the cause your plant died!

This text is not complicated to read

but it does set out to explain where these plants are found in nature

and how Mother Nature grows these species.

For reasons not fully understood, many growers refuse to accept Nature's

advice and as a result many specimens needlessly die. Nothing explained in

this article will cause you to have to do excessive work, only

to modify the way you pot and treat a specimen in your home.

The Kemper Center, Missouri Botanical Garden:

"Spathiphyllum is Greek for leaf-spathe, referring to the character of the spathe, which is the bract or leaf surrounding or subtending a thick protruding flower cluster."

All Peace Lily plants are

members of the genus Spathiphyllum. Many of us commonly grow

a Peace Lily in our

homes

and regardless of the hybrid or species you grow the majority originated

when collectors

went to South America in the 1800’s seeking new and interesting “house plants” for European growers. Although

there are quite a few species, only a few have been grown from the few

species that originated in Asia.

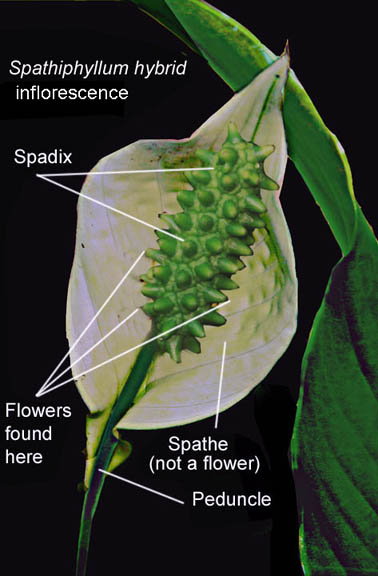

All Spathiphyllum species, as well as all the hundreds of hybrids

and cultivars are

members of the larger plant family known as Araceae, commonly called an

aroid. Aroids are easily recognized by the spathe and spadix

produced by these plants that is incorrectly called a flower.

homes

and regardless of the hybrid or species you grow the majority originated

when collectors

went to South America in the 1800’s seeking new and interesting “house plants” for European growers. Although

there are quite a few species, only a few have been grown from the few

species that originated in Asia.

All Spathiphyllum species, as well as all the hundreds of hybrids

and cultivars are

members of the larger plant family known as Araceae, commonly called an

aroid. Aroids are easily recognized by the spathe and spadix

produced by these plants that is incorrectly called a flower.

The Spathe

or "Peace Lily" can be an excellent houseplant.

Some species and hybrids have often small, narrow lanceolate (lance shaped) leaves while others

have much larger and broader leaf blades. Some produce small

inflorescences while others produce a spathe and spadix that is quite

large. Not all wild Spathiphyllum species are suitable as house

plants but a large number of these white cup shaped spathe bearing

plants are sold as hybridized "Peace Lilies". Virtually none of the

commonly available plants are species but instead are hybrids.

Correctly the term is spathe, not "spath".

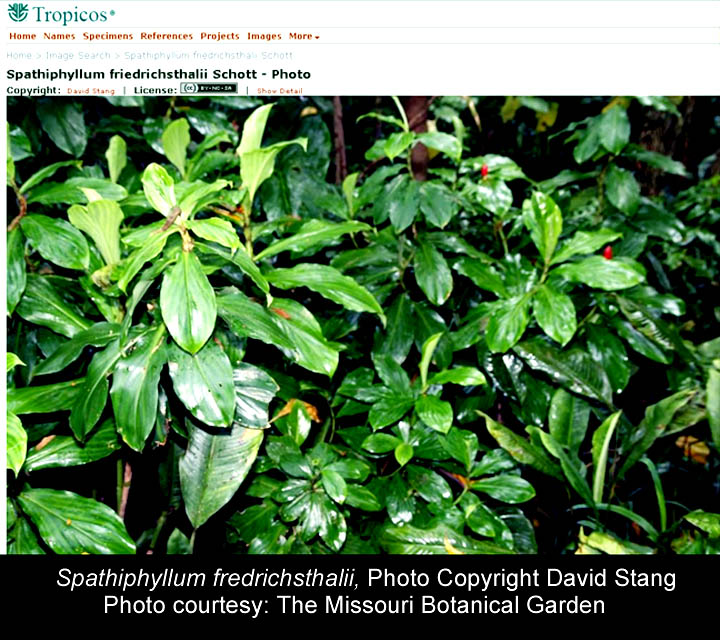

Dr. Nancy Greig PhD, Curator of Entomology at the Houston Museum of Natural Science recently wrote to us and stated, "I am very familiar with Spathiphyllum friedrichsthalii in Costa Rica. It grows in open areas (large rainforest gaps and in swampy fields) in full sunlight, and usually in several inches of water. If you do a Google image search for Spathiphyllum friedrichsthalii you will see a “flickr” photo – that photo is of the “swamp” at La Selva Biological Station La Selva Biological Station in the Atlantic lowlands of Costa Rica (ne quadrant). The people in the photo are standing on the boardwalk that leads through the swamp, which is flooded with several inches of water for most of the year, except at the height of the dry season The dominant plant in the swamp, as you’ll see in the photo is S. friedrichsthalii. S. friedrichsthalii is common in the deforested fields throughout the area."

For

those that don't believe the plants in this genus love water please take

a moment to look at one single photo. The photo of the plants Dr.

Nancy was referring to as standing in water can be seen here:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/codiferous/417124810/

For

those that don't believe the plants in this genus love water please take

a moment to look at one single photo. The photo of the plants Dr.

Nancy was referring to as standing in water can be seen here:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/codiferous/417124810/

A good deal of the information below was derived from the scientific paper the SYNOPSIS OF THE GENUS SPATHIPHYLLUM (ARACEAE) IN COLOMBIA by Felipe Cardona as well as many other scientific documents along with personal communication with the authors noted.

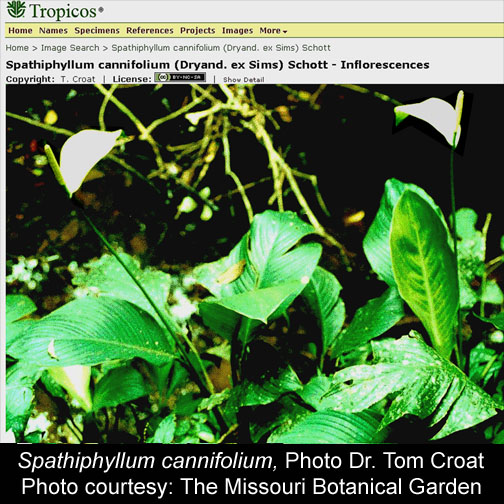

The most likely used species to create the hybrids we grow appears to be one of several including Spathiphyllum wallisii , Spathiphyllum floribundum, Spathiphyllum friedrichsthalii or Spathiphyllum cannifolium which are among the most widespread species in Colombia and some other portions of South America. It is certainly possible Spathiphyllum friedrichsthalii , which is common to Costa Rica has also been used to create some hybrids. The spathe (flower) of Spathiphyllum floribundum and Spathiphyllum cannifolium are close matches to the spathe we observe on many of our hybrid houseplants. Spathiphyllum cannifolium appears restricted to the Amazon basin where it is known from practically all major tributaries of the Amazon basin, at least in Colombia. Within Colombia, Spathiphyllum cannifolium occurs at 200 to 1000 meters (660 feet to to 3,280 feet) in elevation, in tropical wet forest life zones and produces an inflorescence almost any time of the year.

Spathiphyllum minor

is found in tropical wet rain forest at 200 to 300 meters elevation but

normally flowers only in

January. March. July, and September. At

the same time Spathiphyllum perezii is a tropical wet rain forest

species found at roughly the same elevation as Spathiphyllum

cannifolium but blooms in May, July, and September.

Spathiphyllum silvicola is found in both rain forests and

tropical wet rain forests but blooms more

erratically in January,

February, July, September, October and December. Spathiphyllum

lancaefolium grows in wet rain forest and produces inflorescences

from July through October. As you can see, there is no set season

of the year for a specific plant, especially a hybrid to bloom! All of this will

be put into perspective as our discussion of the production of

inflorescences continues.

Please read once again where and how these species commonly grow in nature.

January. March. July, and September. At

the same time Spathiphyllum perezii is a tropical wet rain forest

species found at roughly the same elevation as Spathiphyllum

cannifolium but blooms in May, July, and September.

Spathiphyllum silvicola is found in both rain forests and

tropical wet rain forests but blooms more

erratically in January,

February, July, September, October and December. Spathiphyllum

lancaefolium grows in wet rain forest and produces inflorescences

from July through October. As you can see, there is no set season

of the year for a specific plant, especially a hybrid to bloom! All of this will

be put into perspective as our discussion of the production of

inflorescences continues.

Please read once again where and how these species commonly grow in nature.

A complete list of all the accepted species of Spathiphyllum can be found near the bottom of this page. If a particular name is not on this list it is likely either a hybrid or a plant that has been reduced to a synonym of one of the accepted species' names.

Wet, damp or

dry?

What is the natural

growth of the "Peace Lily" and what does Mother Nature appear

to recommend?

The "Peace Lily" can be found in many leaf blade shapes and sizes.

According to George Bunting’s

A Revision of the Genus

Spathiphyllum

the largest species,

Spathiphyllum commutatum

from Malaysia, the Solomon Islands and parts of Asia, grows to 85 cm (33.4

inches) long and the species

Spathiphyllum cochlearispathum

from Mexico can grow to 80 cm (31.5 inches) long.

Of all the species found in the genus

Spathiphyllum,

all but three are found only in the New World Neotropics. Those three

species are found in the Philippine and Molucca Islands, New Guinea, Palau,

New Britain, and Solomon Islands while all the rest are found from tropical

Mexico through Central and South America.

The "Peace Lily" can be found in many leaf blade shapes and sizes.

According to George Bunting’s

A Revision of the Genus

Spathiphyllum

the largest species,

Spathiphyllum commutatum

from Malaysia, the Solomon Islands and parts of Asia, grows to 85 cm (33.4

inches) long and the species

Spathiphyllum cochlearispathum

from Mexico can grow to 80 cm (31.5 inches) long.

Of all the species found in the genus

Spathiphyllum,

all but three are found only in the New World Neotropics. Those three

species are found in the Philippine and Molucca Islands, New Guinea, Palau,

New Britain, and Solomon Islands while all the rest are found from tropical

Mexico through Central and South America.

The next time someone tells you your "Peace Lily" doesn't like water and should only be given a "drink" when it begins to "beg" suggest they take a trip to Ecuador where they commonly live in streams. I always advocate to "listen to Mother Nature, since her advice is best" and Mother Nature's advice is to keep your Spathiphyllum slightly damp at all times and grow it in bright light. However, it is very true that excess water in the soil can quickly cause the leaves to blacken, especially from the edges before they die. The cause and cure are explained below but be aware the same can happen when a plant is kept far too dry. These plants are water members of a genus that love water since they grow in a rain forest as well as in and along the margins of streams and rivers as can be seen in the photo (left).

The genus is well represented in the South American country of Colombia and is found from near sea level to approximately 1300 meters (4,200 plus feet). The genus is most common in lowland primary forests and is commonly associated with water and streams growing in large colonies that are interconnected by their rhizomes. The genus Spathiphyllum also grows in partially or periodically flooded forests sometimes in sites with relatively low light intensities. However, the assumption these plants will always prosper in low light needs further consideration and explanation. Consider all the scientific evidence as this article progresses.

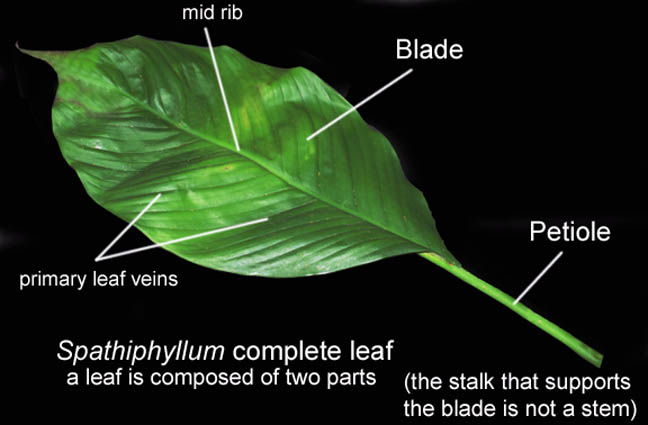

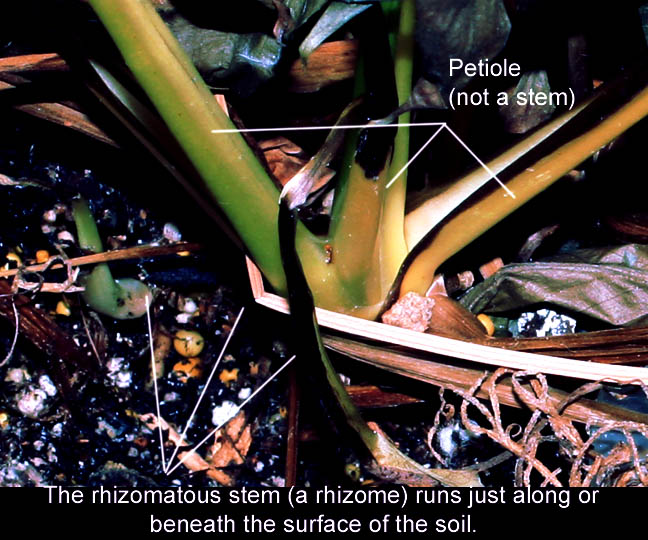

An explanation of the terms rhizome, petiole and stem are in order since the terms also tells us something about how to plants survive and reproduce in nature.

A rhizome is

simply a stem that runs across the surface of the ground and serves as the

primary support or central axis of the plant (photo below). All or most of the

plants in a colony are connected to some degree via their rhizomes.

The terms stem and rhizome are poorly understood by plant growers so it is

important you understand we are not discussing the support of any single

leaf, correctly known as a petiole. Growers are commonly mislead into

believing a leaf is supported by a "stem" but that assumption is incorrect.

Leaves are divided into two primary parts and the two parts growing together are

defined as a "leaf". The two parts are the petiole and the blade.

A rhizome is

simply a stem that runs across the surface of the ground and serves as the

primary support or central axis of the plant (photo below). All or most of the

plants in a colony are connected to some degree via their rhizomes.

The terms stem and rhizome are poorly understood by plant growers so it is

important you understand we are not discussing the support of any single

leaf, correctly known as a petiole. Growers are commonly mislead into

believing a leaf is supported by a "stem" but that assumption is incorrect.

Leaves are divided into two primary parts and the two parts growing together are

defined as a "leaf". The two parts are the petiole and the blade.

The stem is

the base, central axis and main support of a plant normally divided into

nodes and internodes. The nodes often produce roots, leaves its axils, and

the interesting spathe "flower) which is supported on a stalk known as a

peduncle. A node is the point

where the plant produces its roots and hold buds which may also grow into shoots of

various forms. The stem's roots then anchor the plant either to the

ground, a tree or to a rock depending on the species and genus. In the case of the genus

Spathiphyllum a stem may even spread as a repent rhizome creeping across

the soil but is often just beneath the surface. Stems may either

grow above ground, underground or partially above the soil.

According to Dr. Thomas B. Croat who is the Curator of Botany at the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis, MO, in a 1988 paper he stated the species of this genus are found in wet to swampy areas of forests. Additionally, they are found growing along streams or in open swampy areas and live primarily as terrestrial plants. However, they may be hemiepiphytic or even epilithic. An epilithic plant is one that is attached to rock or stone while a hemiepiphyte is a plant that normally begins life on the ground and then climbs a tree. However, if it looses its root connection to the soil it then becomes a epiphyte which is not described in this genus. There are other forms of hemiepiphytes as well but a discussion not appropriate at this point.

Unless you have observed these species in nature and are scientifically qualified to say conclusively that Spathiphyllum species don't like water, we would suggest you may want read more in an effort to learn why there are so many myths about these plants found on the internet. This article also attempts to explain why so many house plant growers have freely accepted these common myths. If you do have scientific credentials and differ we would love to have your detailed explanation so we can share it with the scientists quoted on this page.

In the text the SYNOPSIS OF THE GENUS SPATHIPHYLLUM (ARACEAE) IN COLOMBIA, eighteen species of Spathiphyllum are known to exist in Colombia. Of those, Spathiphyllum cannifolium is “likely the most widespread species of the genus in Colombia. Spathiphyllum cannifolium appears restricted to the Amazon basin, where it is known from primarily all major tributaries of the Amazonas, Cacquetá, Vichada. Apaproris, and Guayabero Rivers. A large gap in distribution exists, however, in ihe central portion of the Colombian Orinoco and Caquetá valleys, likely due to poor collecting in the area. In Colombia, Spathiphyllum cannifolium occurs at 200 to 1000 meters elevation, in tropical wet forest life zones, and flowers all year round.”

On page 50 in his 1978 article

published in the scientific journal Aroideana entitled The Genera of

Araceae in the

Northern Andes

by Dr. Michael Madison formerly of the

Marie Selby Botanical Gardens he states,

"Spathiphyllum

includes 40 species of terrestrial herbs which usually are found in wet

habitats."

Since the date his article was published several new species have been

described to science but the plants we normally grow are rarely species

plants. The number of species has since been revised.

On page 50 in his 1978 article

published in the scientific journal Aroideana entitled The Genera of

Araceae in the

Northern Andes

by Dr. Michael Madison formerly of the

Marie Selby Botanical Gardens he states,

"Spathiphyllum

includes 40 species of terrestrial herbs which usually are found in wet

habitats."

Since the date his article was published several new species have been

described to science but the plants we normally grow are rarely species

plants. The number of species has since been revised.

Again in Aroideana Volume 5, page 117 in an article by Robert White on West Panama he writes, "As we left the area we stopped at a sunny stream and found growing along its banks a small Spathiphyllum sp. with very dark green leathery leaves. The outside of its spathe was dark green and the inside was white, cut with fine lines of green." Aroideana is the journal of the International Aroid Society.

Practical experience quickly teaches a grower Spathiphyllum species and hybrids do best if kept slightly damp in fast draining soil. Not wet. Never dry. The explanation follows,

An important definition you need to understand: Autotrophic

Chlorophyll is the green pigment in every plant that captures sunlight to produce photosynthesis. Plants survive due to photosynthesis Plants draw in carbon dioxide through their leaves and utilizing a process known as being an autotroph they combine CO2 with water that enters the cells of the leaf as a result of rainfall. Autotrophs including Spathiphyllum create their own food by utilizing photosynthesis. If kept in very dim light you are deliberately starving the plants from the ability to produce their own natural sources of food. The process is also known in science as CO2 Fixation or the PCR Cycle (Photosynthetic Carbon Reduction) and in excessively dim light the process of photosynthesis can be switched off.

The process is completed through reduction (stripping away) of carbon dioxide by adding the hydrogen component of water (H2O) to create organic compounds. In biology the term reduction indicates the hydrogen is removed from the oxygen by specialized cells in the leaves. In green plants an autotroph converts physical energy from sun light into carbohydrates in the form of sugars. They may also form chemical energy by synthesizing complex organic compounds from simple inorganic materials in order to produce fats and proteins from light.

The products of photosynthesis produced in the leaf are both sugar and oxygen and the oxygen is given back to the environment while the carbohydrates are used to feed the plant's own growth. Home growers often recommend a Spathiphyllum for this very reason since they feel it will improve the oxygen level in a room.

Although home growers rarely understand or just ignore the need for brighter light and high humidity to grow their plants, stronger light and misting are important to healthy growth. The next time anyone tells you dim light helps this plant or misting is not important since the water evaporates too quickly, recommend they read up on "autotrophic" growth and photosynthesis. It should also be understood plants also need oxygen and draw it in through their roots as will be explained later in this article. For a detailed explanation of the process of CO2 reduction seek a copy of Photobiology of Higher Plants by Maurice S. McDonald in your local library.

Why doesn't

my Peace Lily plant bloom all the time?

There is several reasons and you are not likely the cause!

I recently read a post where a grower indicated if their new plant

didn't produce blooms as she expected it to do she

would "beat it into

submission". Regrettably, that is the way far too many of us think

about our tropical plants.

Although we tend to think of the Spathiphyllum plant always being

filled with inflorescences, in South an Central America is is far more

common to find them "in bloom" from May through November. (Baker

and Burger, Spathiphyllum in Costa Rica, 1976), but many species

commonly have shorter periods of bloom time. Go back up and read

the explanations of the flowering of Spathiphyllum cannifolium,

Spathiphyllum minor, Spathiphyllum silvicola, and

Spathiphyllum perezii. Every species has a bloom period

assigned by Mother Nature.

would "beat it into

submission". Regrettably, that is the way far too many of us think

about our tropical plants.

Although we tend to think of the Spathiphyllum plant always being

filled with inflorescences, in South an Central America is is far more

common to find them "in bloom" from May through November. (Baker

and Burger, Spathiphyllum in Costa Rica, 1976), but many species

commonly have shorter periods of bloom time. Go back up and read

the explanations of the flowering of Spathiphyllum cannifolium,

Spathiphyllum minor, Spathiphyllum silvicola, and

Spathiphyllum perezii. Every species has a bloom period

assigned by Mother Nature.

True, there are species such as Spathiphyllum cannifolium and Spathiphyllum floribundum that commonly produce inflorescences but there is no way to know for certain if the plant you are growing was bred from those species. The chances are high your plant was produced in a chemical soup and its parents were interbreed with many parent species. You are highly unlikely to be growing a true species. Breeders attempt to inbreed plants that tend to produce inflorescences more frequently but in time the plants often return to their in-built DNA coding and produce only on their specific natural schedule. When a breeder is trying to produce plants with spectacular leaves combined with frequent flowering, something has to be given up its natural genetic sequence. Many plants will forever attempt to return to the DNA of their natural parentage.

If you wish to make a specimen

thrive and grow in your home a specimen prefers high humidity

and constant moisture. A specimen should be kept in bright light

but out of direct sunlight

with a tray of pebbles filled with water beneath the pot to provide

some humidity. Although few wild species produce an

inflorescence year round if you

wish

to keep it producing inflorescences the plant should also be misted

frequently. But there may be both a natural and a chemical cause once your plant

begins to refuse to "bloom".

to keep it producing inflorescences the plant should also be misted

frequently. But there may be both a natural and a chemical cause once your plant

begins to refuse to "bloom".

On a visit to the Missouri Botanical Garden research greenhouse in December 2009 not one of the specimen plants of true Spathiphyllum species was producing an inflorescence! These species often bloom seasonally and December was not a part of their bloom season,

Hybridized Spathiphyllum commonly sold in garden and discount

centers can be seen with a cluster of open inflorescence virtually any

month of the year. Commercial growers use a chemical known as

gibberellic acid often sold as GA3 to induce the plants to produce

inflorescences in order to make them more saleable. Gibberellic acid is

a natural plant hormone and is used in agriculture to stimulate both

cell division and cell elongation that affects the leaves as well as the

stems of a plant.

Gibberellic acid is used commercially to make all the plants in one

group bloom at the same time. Through repeated use these large growers

force the growth of a spathe and spadix regardless of season. They have

calculated the quantity to be used and know how much gibberellic acid to

apply to any particular species but these formulations are often guarded

secrets. The next time you buy a beautiful Spathiphyllum at

a discount store and find it begins to produce few or odd shaped leaves

and spathes there may be a reason. The specimen has likely been fed

gibberellic acid since it was nearing sexual maturity to force it to

bloom. Without the constant use of the hormone the specimen cannot get

its "fix" and as a result may rarely bloom again since it has been

"hooked" on the chemical!

Gibberellic acid is used commercially to make all the plants in one

group bloom at the same time. Through repeated use these large growers

force the growth of a spathe and spadix regardless of season. They have

calculated the quantity to be used and know how much gibberellic acid to

apply to any particular species but these formulations are often guarded

secrets. The next time you buy a beautiful Spathiphyllum at

a discount store and find it begins to produce few or odd shaped leaves

and spathes there may be a reason. The specimen has likely been fed

gibberellic acid since it was nearing sexual maturity to force it to

bloom. Without the constant use of the hormone the specimen cannot get

its "fix" and as a result may rarely bloom again since it has been

"hooked" on the chemical!

Although GA3 can be purchased, the use of the chemical can be hazardous to the plant if you don't know the exact dose to use. In that case you must resort to the use of a good fertilizer but never use one in excess.

Are you

growing a species or a hybrid?

Often given as a funeral plant, the "Peace Lily" is a member of the

larger plant family Araceae commonly called an aroid.

The Spathiphyllum hybrid is one of the more commonly

available plants sold in discount stores, nurseries and floral

stores.

True species plants are a very rare

find in the home since almost all available for sale were created by hybridizers.

Even in the wild some species are also quite rare. Almost

all the plants available for purchase were not grown from seed but were

grown in a test tube as a chemically created tissue cultured or cloned

plant. Although I had at one time been led to believe the cloned

variations were "designed" to need little water, that is nothing more

than a myth. The plants can naturally withstand

abuse since they

must live through the dry season in their native habitat which at times

requires them to survive when little water is available but they do have

limitations and cannot withstand perpetual abuse and neglect in a home.

abuse since they

must live through the dry season in their native habitat which at times

requires them to survive when little water is available but they do have

limitations and cannot withstand perpetual abuse and neglect in a home.

One of the more recent additions to the market include a "variegated" form of Spathiphyllum. Variegation is not a common event for these species in nature and is being created in the tissue culture laboratory by injecting a harmless virus known as the Colour Break Virus into the tissue culture mixture. In almost all cases the plant will eventually outgrow the injected virus and will return to the normal green form. This virus is the cause of all variegated plants and is now commonly in use since buyers will often pay extra for a variegated specimen without realizing the variegated colors will likely soon be lost.

Once you read what I attempt to explain

about the "Peace Lily" some will undoubtedly want to say the plants

in our homes are very different from the plants in the rain forest since

they are “house plants” and not wild. Some of literally attempted

to "laugh my explanations on this subject off internet plant discussion

sites". I don't wish to be unkind but all

house plants had to originate somewhere in the wild and just because you

move it into a home does not mean you have changed its genetic makeup!

Your "Peace Lily" house plant may be a hybridized form of a wild plant but the DNA

came from a wild specimen somewhere in the world almost certainly

Central or South America. That plant “remembers”

how it grows in nature and craves for those conditions. When we kill

these plants it is highly likely they died because we fail to treat them the

way their DNA code expects to be treated. If the plant can't get what it

needs including high humidity, at least moderately bright light and

adequate water its response is often to just give up and die. You can easily

avoid that eventuality by giving the plant what it needs! You can

take the plant out of the rain forest but you can't change it into

something that is not already embedded in the DNA coding.

Soil in the rain forest versus the soil you buy

Some years ago I coined a slogan for use in our atrium which you may have read at various places on the internet, "Much of what we believe is based on what we have yet to be taught. Listen to Mother Nature. Her advice is best." I trust you will read everything on this page with that in mind. People believe what they do about growing Spathiphyllum because someone that did not do good scientific research on the topic stated it somewhere and it has since been accepted by the majority of growers. Many growers prefer to do what is easiest for them, not what is best for the plant. As a result, many growers will defend what they have been taught without ever doing one bit of real research other than to accept commonly held beliefs on the internet.

Have you ever walked into a beautiful botanical garden and said to yourself you’d love to be able to grow plants this way in your home? The truth is you can easily do so provided you are willing to learn how they grow in nature and follow Mother Nature’s lead and that does not need to be difficult. Botanical garden staff members rely on botanists that have observed the same specimens in the wild to tell them what each species needs in order to prosper. At the same time, we typically want only one set of very simple rules requiring that we do little. The two photos just below are of our own Exotic Rainforest private garden in Northwest Arkansas. We have a motto which controls the way every plant is grown, "Listen to Mother Nature, her advice is best".

Advice given on the internet is often not based in science but in assumption. Although you are often told on internet discussion sites to water sparingly and buy a “rich” soil for your tropical plants the soil in the tropical rain forests are typically very nutrient poor and it rains often.

A

great deal of litter falls to the ground where it is quickly broken down

through natural decomposition via earthworms, insects including termites

and fungi. Although we grow our plants in air-conditioned living rooms

where there is little humidity,

in the forest the heat and humidity encourage the further decomposition

of the rain forest leaf litter. The shallow roots of very large trees

then rapidly absorb almost all of this organic matter.

As a result, most of

the nutrients are contained in the trees rather than in the soil.

A

great deal of litter falls to the ground where it is quickly broken down

through natural decomposition via earthworms, insects including termites

and fungi. Although we grow our plants in air-conditioned living rooms

where there is little humidity,

in the forest the heat and humidity encourage the further decomposition

of the rain forest leaf litter. The shallow roots of very large trees

then rapidly absorb almost all of this organic matter.

As a result, most of

the nutrients are contained in the trees rather than in the soil.

Most nutrients that manage to be absorbed into the soil are leached out by the frequent rainfall which leaves the soil infertile and acidic. Trees in the rain forest rarely grow deep roots as is common in North America. It is not uncommon for very large trees to fall in a storm but all the seedlings waiting for the patch of light that is left when a giant falls quickly replace them.

The topsoil layers may be only one to two inches (often less than centimeters) deep but provides only a limited amount of nutrition to the plants. The plant life is lush since the plants store the nutrients inside their own cells as well as produce them via photosynthesis rather than gathering them from the soil. Were you to step into a living rain forest you will find far more plants dangling from the trees than you will ever find growing in the soil. Plants in the forest have adapted to utilize the nutrients from their “brethren” in order to flourish and survive.

When plants decay, others rapidly absorb the nutrients left behind from the dead vegetative matter and reuse all of them. At the same time, we tend to “clean up” our plants and just throw the dead leaves in the trash rather than returning them to our compost for our soil mixtures! The fain forest is naturally poor in soil nutrition which is exactly why farmers that regularly destroy thousands and millions of rain forest acres can only use the rain forest soil for one or two years. Man often does not think things through logically and just reacts to opportunity. I fear that far too many plants end up in the trash for the same reasons rain forest farmers continue to destroy the plants in nature. We make too many "assumptions" and do little actual research, we just willingly believe what we are told and if the bad information is challenged some choose only to try to discredit the source rather than consider the science.

The rain forest soil is infertile because it averages eons in development and requires constantly being both replenished while those nutrients are quickly used again. Even in the forest there is not enough vegetative material falling to the ground or trees falling, burning and decomposing to make the soil rich enough to grow a crop! The constant rain washes minerals out of the soil that flows down the numerous rivers leaving soil both acidic and nutrient poor. When the soil is exposed to the heat and sunlight it is often turned into red clay in which little can grow. Many of the remaining minerals cannot be utilized so they become useless to plants. There are occasional fertile patches of soil in the rain forest, but they are rarely compacted and often scattered throughout the thick vegetation. It is a completely viable train of thought to believe species such as Spathiphyllum have been caused by their DNA to seek out streams and pools of water since the concentration of useable nutrition is found in the water as a result of decomposition and frequent rain!

The hot and humid

conditions of the forest cause tropical rain forests to be an ideal

environment for bacteria and other microorganisms and since they remain

active throughout the year they quickly decompose matter on the forest

floor. Yet, despite countless years of developing her plants to live

with specific soil, rain and water conditions we want any plant we buy

to suddenly ignore their DNA and yield to our demands for simple care by

simply buying a “bag of soil” without regard to its contents and dumping it into a pot. These are rain

forest plants and they love water! We must learn to adapt our growing

style to meet our plant's needs, not ours.

The hot and humid

conditions of the forest cause tropical rain forests to be an ideal

environment for bacteria and other microorganisms and since they remain

active throughout the year they quickly decompose matter on the forest

floor. Yet, despite countless years of developing her plants to live

with specific soil, rain and water conditions we want any plant we buy

to suddenly ignore their DNA and yield to our demands for simple care by

simply buying a “bag of soil” without regard to its contents and dumping it into a pot. These are rain

forest plants and they love water! We must learn to adapt our growing

style to meet our plant's needs, not ours.

However, as will soon be explained it is neither difficult nor expensive to create a rough duplication of the fast draining soil Nature creates for her plants.

So, what is the problem that causes our plants to die?

It isn't excess water that kills "Peace Lilies" in homes. The

cause of their demise is almost always poor soil that is kept soggy,

poor light conditions, near constant neglect,

lack of nutrients and even more importantly poor soil conditions!

Since these plants grow in areas where heavy rain waters drain the soil

is nutrient rich. All the decayed vegetation releases nitrogen and other

nutrient rich matter into the water. The water then carries those

nutrients to pools of water as

well as creeks and streams. The decayed vegetation causes most of this

water to be low in pH as well as very soft and those pools are filled with a rich

humus of decaying leaves, branches, animal droppings and other sources

of minerals and nutrients that serve as food for the plants.

Spathiphyllum species love food and I'd bet the majority of growers

that lose these plants have either never fed their plants or at

have tried to feed them to death! Over feeding is just as bad as never

feeding. Good soil mixes are discussed later in this article as

are the reasons most of these plants actually die.

Some try to explain this simple method of growing the Peace Lily on plant forums but they are sometimes all but "laughed" off the page. I am unsure if people don't wish to believe what science explains or have simply made up their mind and don't want to learn anything other that what a friend or family member has regrettably explained incorrectly. Simply because a grower tells you they "know someone" that lost a beautiful Spathiphyllum due to too much light or over watering that does not indicate the plant actually died of too much water and light! Do your own research and don't restrict yourself to plant growing forums! We list many sources you can read on this page.

Long held beliefs are common in home horticulture and some become "old wife's tales that simply will not die. The photo near the top of this page is our artificial Ecuadorian river and almost all the plants along the back are Spathiphyllum. The top is filled with plants that grow along the banks of streams and rivers in South America as well as in shallow water while the plants at the bottom are all aquatic. Although difficult to see the tank contains two mated Angelfish and almost four dozen Neon Tetras.

No Tricks. Just Mother

Nature's Method

(and you don't need to

buy an aquarium.)

For those tempted to say we must be using some "trick", some of the plants have been in our collection for five years or more and others were bought at a local home supply store. All the soil was removed and the plants are "potted" bare root in plastic boxes with suction cups holding them to the back of the aquarium, The boxes have numerous holes to allow the water to freely flow through the roots and the "medium" is nothing more than orchid bark along with fine pieces of charcoal. All the boxes now have roots hanging out the holes reaching the sand on the bottom of the tank.

According to

the Royal Botanic Garden Kew (London) scientific website CATE Araceae, there are

forty five natural species (excluding natural variations)

http://www.cate-araceae.org/Spathiphyllum

However, other

qualified sources offer other numbers for the total species that exist.

Science is constantly changing.

Science is constantly changing.

On top of that there are well over 200 hybridized varieties created by the hand of man, many sold as Spathiphyllum

'Clevelandii' or other made-up names. Like many others, Spathiphyllum 'Clevelandii' is a trade name

and not a species name. As a result it is almost impossible

to look at any specimen and accurately determine what the parent species

may have been.

You can see a complete list of species near the bottom of this page but

you can also see a list of all the names species as well as synonym

names of Spathiphyllum on

the Missouri Botanical Garden website TROPICOS. Please be aware

that many of these scientific names have been sunk into synonym with

other previously described species and are no longer valid. A synonym is a plant that was

described to science after the accepted species name

was described and

has proven to be the same species. During the 19th century this

practice was common since botanists did not possess the scientific

information available today and were not aware of natural variations in

species:

Spathiphyllum species

Light.

Literally the

difference between life and death to a plant.

Spathiphyllum specimens are sometimes known by home growers for

their presumed ability to tolerate low light conditions. As a

result, many home growers expect them to

"tolerate" those conditions for an eternity. Most plant

sellers have little or no training in the science of plants, only the

business of selling them so it is not uncommon to receive poor advice

when you buy one.

For

those that have already drawn the conclusion I am attempting to prove

these species cannot live in shade, please read ths quote from

the

SYNOPSIS OF THE GENUS SPATHIPHYLLUM (ARACEAE) IN COLOMBIA,

"Spathiphyllum

species occur along river banks, on loose clay or sandy soils in shady

areas. Such habitats are more common in the interAndean valleys below

13(K) m than on the rocky river banks of the Chocri region. More

research on the ecology of the species and more extensive collecting,

nevertheless, are necessary before a solid hypothesis can he formulated

to explain the distribution of the genus in Colombia."

For

those that have already drawn the conclusion I am attempting to prove

these species cannot live in shade, please read ths quote from

the

SYNOPSIS OF THE GENUS SPATHIPHYLLUM (ARACEAE) IN COLOMBIA,

"Spathiphyllum

species occur along river banks, on loose clay or sandy soils in shady

areas. Such habitats are more common in the interAndean valleys below

13(K) m than on the rocky river banks of the Chocri region. More

research on the ecology of the species and more extensive collecting,

nevertheless, are necessary before a solid hypothesis can he formulated

to explain the distribution of the genus in Colombia."

Obviously, these species can live in shade. Even though Spathiphyllum can and do tolerate poor conditions does not mean they prefer them. In nature it appears they prefer medium or bright indirect to direct light as well as adequate water and food. However, the genus is sometimes found in full shade as was also described by Dr. Croat in one of his treatments on the species Spathiphyllum dressleri. "Spathiphyllum dressleri ranges from Panama to Colombia and occurs in moist to wet forest, at 50 to 700 meters. The species is rare and is found in full shade in areas of tropical wet forest." Be sure and pay attention to the part about "moist to wet forest".

Full shade does not indicate a plant should be eternally stuck in a darkened corner of a room either. In the forest tropical plants are living beings that are capable of slowly transporting their colony to better conditions when their current placement becomes inhospitable. Those that can climb trees just climb higher but Spathiphyllum must use another method.

It is not uncommon for the forest canopy to encroach on bright to moderately bright light to the point the understory plants that live on the ground cannot gather enough light to survive. Since Spathiphyllum species spread as they reproduce and grow they simply begin to reproduce themselves away from the shade and each new growth shares its stored sunlight with neighboring plants via their underground connections. A colony of wild Spathiphyllum is one single giant organism composed of many individual plants.

If

your plant is stuck in a dark corner it stays there until you choose to

move it! The plant has no natural way to correct its poor growing

conditions and once the light level is intolerably inadequate for the

production of sufficient sugars in order to feed itself the plant simply

runs out of options and cease to survive thus providing more compost to

the forest floor to feed all the remaining plants. It happens all

the time in nature, and too often in homes.

If

your plant is stuck in a dark corner it stays there until you choose to

move it! The plant has no natural way to correct its poor growing

conditions and once the light level is intolerably inadequate for the

production of sufficient sugars in order to feed itself the plant simply

runs out of options and cease to survive thus providing more compost to

the forest floor to feed all the remaining plants. It happens all

the time in nature, and too often in homes.

How do

plants such as a Spathiphyllum know to seek brighter light, quite

simply their own DNA points them in that direction and in the case of

many climbing species towards a tree to climb. Many rain forest

plants need a tall tree tree so they can begin their climb toward the

light in order to attain adulthood and nature provides with with a

unique tool known as scotopism to seek dark shade in order to climb a

tree to brighter light. However, in the case of the "Peace Lily", the

species is a water loving terrestrial species and is rarely found

growing in trees.

Once the plant realizes it has insufficient light to produce adequate

food its own DNA tells the group of plants it is time to move in order

to find more "food" in the form of light. Plants need brighter light

source in order to produce more chlorophyll and thus more sugar.

Chlorophyll is the green pigment in every plant that captures sunlight

to produce photosynthesis. Plants draw in oxygen through their roots and

carbon dioxide through the leaf blades. As explained earlier, the carbon dioxide (CO2)

combines with water that enters the cells of the leaf in the form

of humidity and rain. The oxygen is given back to

the environment for all living beings to breathe and the sugar is used

in the form of carbohydrates to feed and nourish the plant's own growth.

Stronger light is essential to the healthy growth of every

Spathiphyllum plant in the same way it is essential to all others.

Plants don't truly "make" oxygen, they simply release it through

photosynthesis.

Were you to borrow a very good light meter from a trained professional photographer and do the math you would learn the light level in a darkened corner of a living room is less than 5% (perhaps lower) than the bright light these species enjoy in nature. Ask a good photographer to help you understand the concept of light reduction when using a camera. Assuming a good camera has f/stops ranging from f/22 down to f/2.8 (a normal 6 f/stop range), every time you make a one stop adjustment you have lost 50% of the previous amount of measured light. If you have to use the f/22 reading in the sun which would be normal in most situations but must also use the f/2.8 setting in the living room (again normal), you have just lost more than 95% of the available light!

Should I

really water the plant or let is stay dry most of the time?

I

frequently read posts on garden forums asking why a “Peace Lily” is

about to die and how to save the plant. Almost

without exception the principal responses given are to slow down on the

water and/or move it to an area of dimmer light. This advice is exactly the

opposite of what nature provides naturally!

I'm not certain where

such advice on the the "Peace Lily" originated but if you

missed all the opening remarks in this article you should be aware this plant commonly grows

either in water or on the edges of pools of water in moderately bright

light in the native habitat. If a grower moves the plant into dim light the

eventual result mayt be the demise of the plant since it can no longer

complete its natural photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is a

requirement of the plant to keep it alive and healthy!

I'm not certain where

such advice on the the "Peace Lily" originated but if you

missed all the opening remarks in this article you should be aware this plant commonly grows

either in water or on the edges of pools of water in moderately bright

light in the native habitat. If a grower moves the plant into dim light the

eventual result mayt be the demise of the plant since it can no longer

complete its natural photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is a

requirement of the plant to keep it alive and healthy!

Although these plants are tolerant of neglect they can't survive

forever if not allowed to live as they were intended to live and grow. A

great rule to follow is "Listen to Mother Nature since her advice is

best" and Mother Nature gives the plant adequate light, food and water.

One of the most brilliant friends I have is aroid botanist Dr. Tom Croat. Tom has personally collected more than 100,000 living specimens n

the wild and granted scientific names to more aroid species than any

other living human on this Earth. Tom has often called Spathiphyllum

species “water hogs”!

Despite the fact people are constantly advised to grow these plants dry

and in dim light I've spoken with aroid botanists including Tom that

have seen these plants growing in very bright light away from the edges

of the canopy shade. The wild “Peace Lily” often stands in water.

My friend and naturalist Joep Moonen who lives in French Guiana which is

an extremely tropical nation in the northeastern corner of South

America. Joep (pronounced "yupe") recently wrote,

"We have

Spathiphyllum humboldtii growing in French Guiana but it is very rare.

It grows in gravel on creek banks and in the rain season grows partly

under water."

That

beautiful spathe. Is it really a flower?

Spathiphyllum species are common to much of Central and South

America as well as s few species in Southeast Asia. Although it is commonly called a “Peace Lily” the plant is in

the family Araceae. Plants are divided into

classes, subclasses, orders, families, genera (genus) and species. The

family which is at the top of the list for Araceae is Liliopsida.

Spathiphyllum species are not in the family Liliaceae which contains

most of the lily species although both Liliaceae and Liliopsida are

related Monocots so the common name is somewhat misleading. The common

name “Spath” comes from the spathe the plant produces which is one of

the major parts of the inflorescence used for reproduction.

Aroids are characterized by the growth the inflorescence known to

science as a spathe surrounding a spadix. Despite being called a "flower"

the spathe is not a flower and is simply a modified leaf

which appears in the shape of a hood. The spadix is located at the

center of the inflorescence and is a spike on a thickened fleshy

axis which is supported on a stalk known as a peduncle.

When a “Peace Lily” is referred to as "flowering" the reference is truly

to the very small flowers (near microscopic) which are produced along

the spadix and have nothing to do with the spathe. The only connection is

both are produced during the plants sexual reproduction known as

anthesis. The spathes of different species do not look

alike and some look nothing like the common plant found in a home. Each species has a unique inflorescence which is one of the

main characteristics used to determine the species. Since the

majority of plants sold in the U.S. are hybrids the characteristics of

the inflorescence is likely a combination of both parent species.

The pollination of a Spathiphyllum specimen appears relatively

simple in nature and includes a long flowering cycle.

While aroid

species such as Philodendron are unisexual and possess imperfect

flowers with the female flowers found in a female

floral chamber to hold the female

flowers Spathiphyllum species

possess perfect flowers.

Bisexual

inflorescences possess perfect flowers containing both male and female

sexual organs throughout

the length of the spadix without any distinctive zones.

The pollination of a Spathiphyllum specimen appears relatively

simple in nature and includes a long flowering cycle.

While aroid

species such as Philodendron are unisexual and possess imperfect

flowers with the female flowers found in a female

floral chamber to hold the female

flowers Spathiphyllum species

possess perfect flowers.

Bisexual

inflorescences possess perfect flowers containing both male and female

sexual organs throughout

the length of the spadix without any distinctive zones.

Within the

bisexual inflorescence each tiny section which can be observed on the

spadix with a good magnifying glass is an individual flower consisting

of a central female structure with a stigma at its center and several

male flowers surrounding that stigma. These male flowers are

difficult to observe except during male anthesis when they are actually

producing pollen. The pollinator

of these species is thought be a small bee active only during daylight

hours but the thermogenesis of the species has never been documented.

Thermogenesis is a heat rise produced by the inflorescence that is used

to disperse a perfume-like pheromone in order to attract the pollinating

insect. Insects can also "see" the heat as a result of

infrared heat.

If you'd like to know more about thermogenesis and are interested to learn how aroids are

pollinated please click on this link.

Natural pollination in aroids

Solving the

problem of keeping your Peach Lily happy!

It really isn't hard

but the method won't be popular with some of your friends.

Although it is acceptable to allow a Spathiphyllum to become

slightly root bound, despite commonly given advice, aroids don't like to have their roots

constantly restricted in a tight pot! They need room to easily spread and

grow. Have you ever visited a rain forest and dug up a plant?

You won't find a root ball since there are not pots in the forest! The advice to keep a plant with the roots tightly restricted is based on

a nurseryman's need to have the roots quickly fill the pot in order to

encourage the above soil growth. By continuing to restrict them

into a tight ball you do not allow them to freely grow and stretch as

they would in nature. As a result, after observing many aroids

being repotted by professional growers at major botanical institutions we always loosen the root

system

and use pots that are several inches larger when repotting our aroid

specimens. All are repotted regularly on an approximately every

two year cycle to renew the soil.

So why is the soil mixture important? If the roots of Spathiphyllum

species or hybrids don't have the ability to stretch, grow and move

freely in their soil they will rot. These plants need very loose porous

soil and you aren't ever going to find that in an off the shelf potting

mix. It isn't the water that causes the roots to rot it is the soggy,

sticky, thick, gummy soil growers normally plant them in!

The only way to allow the roots to absorb nutrients, breathe and poke

around easily in the soil is to make it possess a very porous

consistency with lots of easily reached regions that are never tightly

compacted. In the compost-filled silt of a Central American or tropical South American

stream or pond of standing water these plants can run their roots all

over the place. You can often reach into the water and feel only very loose

compost rather than thick gooey mud. For some reason people believe they

can just go buy "potting soil" and anything should grow in it but that

may well be the kiss of death to many tropical plants!

Potting mix companies make it the way they do since they know most people are

going to fail to water their plants properly. Instead of following the

lead of the companies that sell this thick “mud” we need to pot our

plants correctly unless you are willing to constantly sacrifice

specimens and pay good money to a plant retailer for a replacement.

We have kept Peace Lilies alive and well for over 20 years in loose

compost filled soil!

Just as you wouldn't plant a cactus in soggy soil you shouldn't plant a

Spathiphyllum in incorrect soil. Cacti like sandy soil and

Spathiphyllum prefer loose soil that is filled with natural food

(decaying vegetation). We are quick to go out and buy the

right mix for a succulent but never consider doing the same for an aroid

species including a Philodendron or Anthurium even though they also need

a special mixture to prosper.

Once a home grower sees their plant begin to decline the first reaction

after posting or reading a few comments on a garden site is to slow down on the water

without bothering to learn how these plants grow in the wild. Not long

after they come back and post their plant died anyway.

Remember, these are rain forest plant species and they live in an

extremely wet environment. For 6 to 8 months a year it rains much of the

day! Rather than trying to force the plant to do what we want it to do

we need to learn what the plant needs.

I find it regrettable that many home growers are just down right lazy

when it comes to taking care of their plants and use what I believe is

an excuse to make themselves feel better. It sure doesn't make the plant

feel better. If you went out and bought a dog you'd feed and treat it

the way it needs to be fed and treated. Why won't we do that with a

plant?

Good growers mix their soil for each plant to match what the plant needs

in order to make the plant prosper. These species need extremely porous

soil and moderately bright light or their roots may eventually rot. But it isn't

watering that causes the rot and eventual death of the plant. It is the

soil quality, low light which starves the plant of needed chemical

reactions and neglect!

Here is the

secret most serious aroid growers already know!

Here's how to mix your soil for your "Peace Lily" . The more

porous the soil the better! You're going to make up a special soil mixture

using only some off the

shelf soil. If you make your own compost start with that for about 1/3

the total mix and modify the rest of the ingredients. Begin by making

a mixture of about 20% potting soil, 30% peat moss, roughly 20% Perlite, and 30% orchid potting

mix which contains cedar wood chips, charcoal and gravel. To that add

any good compost, a few cups of finely cut pieces of sphagnum moss and

some cypress mulch. If you have some Vermiculite throw that in as well.

This formula isn't critical, just keep it very loose. Mix all of this thoroughly and keep it

constantly damp (never dry)once you pot your plant. Enough ingredients to pot a

large plant shouldn't cost more than $15 and the chances are high you'll

have enough mix left over to plant one or two more plants.

Many

commercial growers really don't care if you kill your plant since you'll

probably go buy another one and that makes

them money. I have large

Spathiphyllum specimens that are almost 20 years old and my atrium is

watered daily to every other day depending on the season of the year.

Only during the middle of winter do we slow down to 2 or 3 days per week. During the summer my plants receive

6 to 8 minutes of

water per per day. I also grown these plants in water and I have

friends that grow them in aquariums. You can even buy them as aquarium

plants in many pet stores and in an article published in Aroideana

volume 3, #4 entitled AROIDS IN THE PUBLIC AQUARIUM, author Craig

Phillips who at the time was the Director of the National Aquarium in

Washington, D.C. described how Spathiphyllum species were used in

some of their aquarium displays.

Although giving the plant enough light to allow it to create its own

food, here's another important factor to keep these plants healthy! Give

your plants a regular dose (follow the instructions, use every three

months) of a 13-13-13 or

14-14-14 palletized fertilizer to keep them producing

inflorescences. Osmoscote is a pelletized fertilzer given once every

three months and available at garden centers. Commercial aroid

growers have learned the mixture works best for aroids.

Fertilizers with lower numbers will not do as well but you may need to

search for the correct mixes! They are not always easily

available.

Growers need to pay attention to what the plant wants and needs

naturally or should not even buy one if they aren't going to treat it

right. Water it but pot it right first. Remember, keep the plant in

bright indirect light, keep the soil evenly damp and feed it! And I'm

sorry if some are offended, but ignore the old wives' tales!

On the internet, people give advice based on what is best for themselves

and not necessarily for the plant. If you want to grow them

successsfully you will need to be wiling to do more than what is easiest

for you.

Healthy growth is about the fast flow of water through the soil. The lack thereof causes a lack of oxygen, anerobic fermentation and saprophytes that turn into pathogens. Saprophytes are organisms including fungus or bacteria that grow on and draw nourishment from dead or decaying organic matter that often includes soggy wet soil. The pathogens attack the roots and cause them to rot so all of the advice to "slow down on the water" is really about how to control the pathogens.

Anoxia, fermentation

and saprophytes

The reason many

house plants die!

Fermentation and saprophytes often occur in muddy soil that will not

not allow the roots to breathe but they don't

necessarily occur in water which is why we can cause a plant that is

about to die to grow new roots in clean water.

As a result, it is necessary to use soil mixes that allow the roots

to breathe and will not remain soggy. I've attempted in

many plant forum threads to explain the necessity of mixing proper soil for

plants but the advice is often ignored since it requires some "work"

on the part of the plant's keeper. The reason plants rot is not the

amount of water given to the plant! These are rain forest plants and

are literally drowned for months at a time! They die due to

anoxia in a pot.

If you could visit a rain forest you would quickly learn the soil is

composed of leaf litter, decaying wood, compost, animal droppings

and the charcoal left behind when a part of the forest burns. If

we'll just listen to Mother Nature we can all make our plants grow

as they do in nature. That is precisely what I attempt to explain

when I recommend mixing soil, not

just buying a bag at the store.

Over time we've arrived at a soil mixture for most of our aroid

species which duplicates the rain forest. We use this mixture on the

advice of the aroid keepers at the Missouri Botanical Garden in St.

Louis. The goal of this mix is to allow the roots to freely find

places to extend and grow without constantly finding wet places

where they will rot. This mix will remain damp but drain quickly.

The common advice on most garden websites is to allow a plant to dry between watering, however that is often not good advice. Here's why.

Anyone that has asthma knows the difficulty of getting air out and then drawing fresh oxygen back in. Even though plants release oxygen into the air through their leaves they draw fresh oxygen into the plant through their roots. A potted plant is much like your lungs and if you can't bring in fresh oxygen you will soon cease to live. Mud blocks the flow of oxygen. So you ask, how do these plants survive in the rain forest where some are observed growing in fairly rich boggy soil on the edges of rivers and streams? There are apparently an almost imperceptible water flow through the roots caused by the water flow of the stream. If you read earlier how jungle soil is made up, you also understand it is very porous and this allows the oxygen to still reach the roots. Mother Nature knows "tricks" we have yet to discover in our homes so we need to play close attention to what she does and duplicate her "style" as best possible.

As a result the top layer of a potted plant's soil should not be allowed to completely dry since that dry soil prevents the intake of fresh air! Remember, unlike jungle soil your pot is solid and no oxygen can enter though the walls as it would with only a tiny amount of water flow in th forest. Once the soil in a pot dries it creates a "blanket effect" to hold in the stale moisture and keep out fresh oxygen. Once the top layer dries the moist layer below cannot easily breathe in order to re-oxygenate the soil so it is possible to soon become anoxic (the lack of oxygen). Anoxia encourages saprophytic growth and leads to root rot,

The dry upper layer surrounded by very solid pot walls actually prevents the capillary effect of the wet surface evaporation when damp soil is exposed to air. When you pour water in the air inside the soil is displaced so the oxygenated air inside has left the pot. If the upper soil layer completely dries the "lungs" of the pot cannot work and can no longer continue to draw in another breath of fresh air including needed oxygen.

The entirety of the soil needs to remain evenly damp so the roots of the plant can continue to draw in fresh oxygen. Otherwise, root rot is likely to begin. Since most people don't want to bother with ever watering their plants, many people go into a garden store and purchase a very rich potting soil that stays soggy all the time. Despite the belief they are giving the plant a "rich" soil to make it thrive they may be dooming their Spathiphyllum specimen to death in anoxic mud. Plant species can literally drown in mucky soil with no air or water motion due to a lack of oxygen that leads to saprophytic growth!

Rather than using a soggy soil and watering only once a week (or less), use a soil that holds moisture well but drains quickly. With the help of botanical garden researchers we've learn to develop a soil mixture for most of our aroid species that works great. People who visit our artificial rain forest are often amazed at the size of many of our specimens that grow much faster and larger than they often do in a home since we water frequently.

A very interesting point was raised a few years ago by my friend Julius Boos (1946 to 2010) from Trinidad. Julius was known widely as an expert in aroid species having published many articles in scientific publications and journals such as Aroideana. Aroideana is the official publication of the International Aroid Society. You may find his quote of interest, "The blooms of Spathiphyllum cannifolium are reportedly used and cooked as an ingredient in curries in Surinam and northern South America. I got a recent record of the blooms and young leaves of Caladium bicolor being cooked and used as a food in Aruba and N. W. Trinidad, W.I. and the name used for them there was 'ca-chew'." So at least some of these plants are used for more purposes than simply as a house plant! Spathiphyllum cannifolium is a unique species of Spathiphyllum.

The hybridized Spathiphyllum ("Peace Lily") is tolerant of a fairly wide range of conditions and abuse for moderately long periods of time but if not potted properly as well as given adequate light will eventually simply give up and die. Even near death, the plant often recovers with little more than a regular watering and a pruning to remove the dead leaves and spathes provided it is given a minimal dose of fertilizer and good light. Although it will be close to dehydration and starvation the plant will tell you when it wants to be watered by beginning to droop its leaves.

If fertilized moderately and treated well a large number of very exquisite green spathes of the Spathiphyllum that is capable of turning white will grow. The lance shaped leaves normally reach 20 to 40cm (8 to 16 inches) in length and grow directly from the soil via the support of their petiole. However, there are numerous hybrids that can grow larger. All plants in the genus prefer medium to moderately bright light so long as it is near a window but protect it from cold and drafts! Spathiphyllum grows nicely under average room temperatures and can easily be propagated by dividing a few of the plant's rhizome clumps as a specimen begins to outgrow the pot.

On the subject of colored spathes, or supposed plants that produce a colorful spathe other than white I asked Dr. Croat on August 15, 2010 to comment. He responded, "Most species actually produce green spathes. Rather few are actually white but no other colors are involved." Just another myth to chalk up to all the others that can read on the internet.

Aroideana is the scientific journal of the International Aroid Society. http://www.aroid.org/

For

information on natural variation in aroid and other plant species please

visit this page:

Natural variation

My thanks to Devin Biggs for the use of his photos. Many aroids can be

grown as semi-aquatic plants under proper conditions. See this website

for information:

http://ripariumsupply.com/

The currently accepted list of

Spathiphyllum species.

Click the species name for additional information.

Spathiphyllum atrovirens Schott, Oesterr. Bot. Z. 8: 179 (1858).

Spathiphyllum barbourii Croat, Rodriguésia 56: 117 (2005).

Spathiphyllum bariense G.S.Bunting, Phytologia 64: 480 (1988).

Spathiphyllum blandum Schott, Oesterr. Bot. Wochenbl. 7: 159 (1857).

Spathiphyllum brent-berlinii Croat, Rodriguésia 56: 118 (2005).

Spathiphyllum brevirostre (Liebm.) Schott, Aroideae 1: 2 (1853).

Spathiphyllum buntingianum Croat, Rodriguésia 56: 120 (2005).

Spathiphyllum cannifolium (Dryand. ex Sims) Schott, Aroideae 1: 1 (1853).

Spathiphyllum commutatum Schott, Oesterr. Bot. Wochenbl. 7: 158 (1857).

Spathiphyllum cuspidatum Schott, Oesterr. Bot. Wochenbl. 7: 158 (1857).

Spathiphyllum diazii Croat, Rodriguésia 56: 121 (2005).

Spathiphyllum dressleri Croat & F.Cardona, Aroideana 27: 139 (2004).

Spathiphyllum floribundum (Linden & André) N.E.Br., Gard. Chron., n.s., 1878(2): 783 (1878).

Spathiphyllum friedrichsthalii Schott, Aroideae 1: 2 (1853).

Spathiphyllum fulvovirens Schott, Oesterr. Bot. Z. 8: 179 (1858).

Spathiphyllum gardneri Schott, Aroideae 1: 2 (1853).

Spathiphyllum gracile G.S.Bunting, Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 10(3): 32 (1960).

Spathiphyllum grandifolium Engl., Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 37: 119 (1905).

Spathiphyllum grazielae L.B.Sm., Fl. Braz. For.: t. 31 (1968).

Spathiphyllum humboldtii Schott, Aroideae 1: 2 (1853).

Spathiphyllum jejunum G.S.Bunting, Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 10(3): 23 (1960).

Spathiphyllum juninense K.Krause, Notizbl. Bot. Gart. Berlin-Dahlem 11: 615 (1932).

Spathiphyllum kalbreyeri G.S.Bunting, Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 10(3): 21 (1960).

Spathiphyllum kochii Engl. & K.Krause in H.G.A.Engler, Pflanzenr., IV, 23B: 123 (1908).

Spathiphyllum laeve Engl., Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 37: 120 (1905).

Spathiphyllum lanceifolium (Jacq.) Schott in H.W.Schott & S.L.Endlicher, Melet. Bot.: 22 (1832).

Spathiphyllum lechlerianum Schott, Prodr. Syst. Aroid.: 425 (1860).

Spathiphyllum maguirei G.S.Bunting, Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 10(3): 23 (1960).

Spathiphyllum matudae G.S.Bunting, Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 10(3): 38 (1960).

Spathiphyllum mawarinumae G.S.Bunting, Phytologia 64: 480 (1988).

Spathiphyllum minor G.S.Bunting, Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 10(3): 31 (1960).

Spathiphyllum monachinoi G.S.Bunting, Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 10(3): 19 (1960).

Spathiphyllum monachinoi var. monachinoi.

Spathiphyllum monachinoi var. perangustum G.S.Bunting, Phytologia 64: 482 (1988).

Spathiphyllum montanum (R.A.Baker) Grayum, Phytologia 82: 50 (1997).

Spathiphyllum neblinae G.S.Bunting, Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 10(3): 25 (1960).

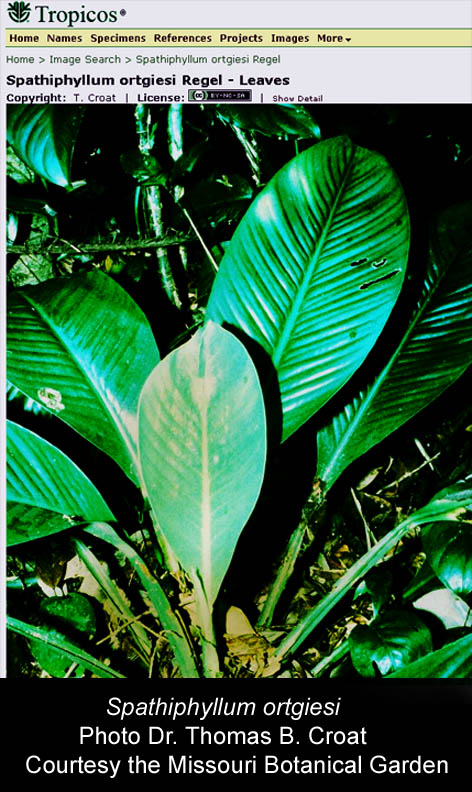

Spathiphyllum ortgiesii Regel, Gartenflora 19: 39 (1870).

Spathiphyllum patinii (R.Hogg) N.E.Br., Gard. Chron., n.s., 1878(2): 783 (1878).

Spathiphyllum patulinervum G.S.Bunting, Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 10(3): 32 (1960).

Spathiphyllum perezii G.S.Bunting, Acta Bot. Venez. 10: 321 (1975).

Spathiphyllum phryniifolium Schott, Oesterr. Bot. Wochenbl. 7: 159 (1857).

Spathiphyllum quindiuense Engl., Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 37: 120 (1905).

Spathiphyllum schlechteri (Engl. & K.Krause) Nicolson, Blumea 16: 120 (1968).

Spathiphyllum schomburgkii Schott, Oesterr. Bot. Wochenbl. 7: 158 (1857).

Spathiphyllum silvicola R.A.Baker, Phytologia 33: 448 (1976).

Spathiphyllum solomonense Nicolson, Amer. Journ. Bot. liv. 496 (1967). 54: 496 (1967).

Spathiphyllum tenerum Engl., Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 37: 120 (1905).

Spathiphyllum uspanapaensis Matuda, Cact. Suc. Mex. 21: 74 (1976).

Spathiphyllum wallisii Regel, Gartenflora 26: 323 (1877).

Spathiphyllum wendlandii Schott, Oesterr. Bot. Z. 8: 179 (1858).