![]()

Aroids and other genera in the Collection

Take the Tour Now?

Orchids

The

Exotic Rainforest

Plants in

the Exotic Rainforest Collection

The images on this website are copyright protected. Please contact us before any reuse.

Detailed information on Growing Anthurium

Species Click this Link

Within our collection we have many species of Anthurium.

If you are seeking other photos,

click this link:

New: Understanding, pronouncing and using Botanical terminology, a Glossary

Anthurium watermaliense Hort. ex L.H. Bailey & Nash

Anthurium watermaliense Hort. ex L.H. Bailey & Nash

scientific species.

However, on the Royal Botanic Garden Kew website

World Checklist of Selected Plant Families

World Checklist of Selected Plant Families

, the Kew's CATE Araceae

and the Kew's World

Checklist of Monocotyledons World

Checklist of Monocotyledons

the name

is an accepted

scientific name.

Some botanists speak of Anthurium watermaliense as a described species while

some do

not. On the weekend of December 11, 2009 I

asked

Dr. Croat his opinion and was assured the plant is a valid species

common to parts of Central America. Dr. Croat is

America's leading aroid botanist.

scientific species.

However, on the Royal Botanic Garden Kew website

World Checklist of Selected Plant Families

World Checklist of Selected Plant Families

, the Kew's CATE Araceae

and the Kew's World

Checklist of Monocotyledons World

Checklist of Monocotyledons

the name

is an accepted

scientific name.

Some botanists speak of Anthurium watermaliense as a described species while

some do

not. On the weekend of December 11, 2009 I

asked

Dr. Croat his opinion and was assured the plant is a valid species

common to parts of Central America. Dr. Croat is

America's leading aroid botanist.The aroid is very common in Costa Rica and Panama and grows terrestrially in the soil. Anthurium watermaliense has been noted to also have been collected in Colombia but appears to be uncommon in that country.

forms, Anthurium watermaliense

is found from sea level to approximately 2500 meters (8000 feet) in

wet pre-mountainous rain forests with the majority of specimens

found at elevations of approximately 750 meters (2500 feet) or less. A "bird's nest" form is an

Anthurium specimen which grows in a rosette shape with the leaves

extending outward from the stem.

forms, Anthurium watermaliense

is found from sea level to approximately 2500 meters (8000 feet) in

wet pre-mountainous rain forests with the majority of specimens

found at elevations of approximately 750 meters (2500 feet) or less. A "bird's nest" form is an

Anthurium specimen which grows in a rosette shape with the leaves

extending outward from the stem. In 2005 Dr. Croat responded to a question on the aroid forum Aroid l regarding the section placement of Anthurium watermaliense, "I have placed this in Section Pachyneurium owing to its involute vernation but it is an unusual member of that group for sure. I have often wondered if it might not be itself of hybrid origin." Dr. Croat then continued, "There are about a half dozen of these cordate odd balls, A. standlyi, A. schottii, etc. Some are quite attractive." Cordate is a reference to the heart shaped leaf and involute vernation refers to the way both margins (edges) of a new leaf blade are rolled inward similar to two tubes as it begins to emerge from the cataphylls which protect any newly emerging leaf blade.

also

stands on a stipe.

The term stipe is a adjective of the term stipitate and indicates

there is a stalk that supports some other structure. You can

clearly see the stipe in the photo to the right as well as the photo

above of a newly forming inflorescence. Please notice that in

both cases the spathe has begun to reflex (turn backwards away from

the spadix.

also

stands on a stipe.

The term stipe is a adjective of the term stipitate and indicates

there is a stalk that supports some other structure. You can

clearly see the stipe in the photo to the right as well as the photo

above of a newly forming inflorescence. Please notice that in

both cases the spathe has begun to reflex (turn backwards away from

the spadix.Leland explains further, "In looking at the detail photos of the inflorescence, notice that the spadix is stipitate. In other words, the spadix is supported by a stipe...the bare portion below the flowers and above the spathe. In the section Pachyneurium the presence of a distinct stipe is rather rare so it is a good feature to point out." In the case of Anthurium watermaliense the stipe emerges white but soon darkens to match the color of the peduncle.

When an Anthurium is "in flower" the reference is to sexual anthesis at which time the spadix produces tiny male, female and sterile male flowers that grow on the spadix. The spathe itself is a modified leaf and is not a "flower". The spadix may be purplish when young but typically turns green to yellowish green or tan-white tinged purple-violet as it ages (see photo below). The spadix vaguely resembles an elongated pine cone and when mature both the spathe and spadix turn so dark in color they appear black, thus the common name "Black Anthurium". The spadix is a spike on a thickened fleshy axis which can produce tiny flowers.

During sexual anthesis the tiny male flowers produce pollen and the very small female flowers become receptive to pollination, however, most aroids are cleverly divided by nature to keep the aroid from becoming self-pollinated. The female flowers reach sexual anthesis first and once they have completed the process the male flowers begin to produce pollen. Nature's preferred method for pollination is to have insects (almost always a beetle from the genus Cyclocephala) to collect pollen from a plant of the same species at male anthesis and carry it to the female flowers of another specimen of the same species at female anthesis in to keep the species strong. Once pollinated the spadix produces berries which in the case of Anthurium watermaliense are ovoid to obovoid in shape and yellowish to orange when mature and will contain the seeds of the Anthurium. For additional information on aroid sexual reproduction please refer to this link: Aroid pollination

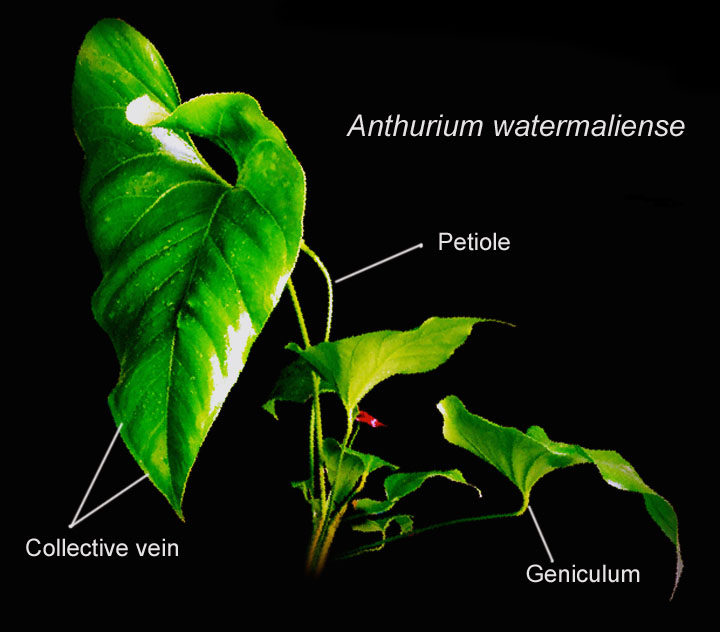

The

deeply lobed cordate leaf blades of

Anthurium watermaliense typically measure 30 to 60 cm (1 to 2

feet) and stand erect on a long petiole. The blades are

sub-coriaceous (less than leathery) to the touch, glossy to

semi-glossy and bi-colorous (two colored)

but

are paler in color on the abaxial (underside) of the blade. The

primary veins are sunken but

weakly raised on the adaxial (upper)

surface but are more prominent on the abaxial (lower) surface.

The primary veins on the blade's underside

are also darker in color. The midrib is narrowly rounded

and slightly paler in color than the blade. The primary veins are sunken but weakly raised

on the adaxial (upper) surface (see photo, left). However, they are more prominently

seen on the abaxial (lower)

surface.

The

deeply lobed cordate leaf blades of

Anthurium watermaliense typically measure 30 to 60 cm (1 to 2

feet) and stand erect on a long petiole. The blades are

sub-coriaceous (less than leathery) to the touch, glossy to

semi-glossy and bi-colorous (two colored)

but

are paler in color on the abaxial (underside) of the blade. The

primary veins are sunken but

weakly raised on the adaxial (upper)

surface but are more prominent on the abaxial (lower) surface.

The primary veins on the blade's underside

are also darker in color. The midrib is narrowly rounded

and slightly paler in color than the blade. The primary veins are sunken but weakly raised

on the adaxial (upper) surface (see photo, left). However, they are more prominently

seen on the abaxial (lower)

surface. Every leaf of an Anthurium is supported by a petiole (photo, right). The petiole is the stalk that attaches the leaf blade to the stem. The petiole extends upward and outward from a node on the stem to the point where it joins with the leaf blade. The petioles of Anthurium watermaliense are terete (rounded) to just less than rounded, may be very slightly speckled and slightly flattened as well as canaliculate on the adaxial (upper) surface (photo, right). Additionally, the petioles are weakly sulcate. Sulcate indicates either a canal known as a sulcus or having numerous fine parallel grooves running parallel along the petiole and canaliculate indicates a channel running the length of the petiole.

Despite

a tendency for collectors to call a petiole "the stem",

that is scientifically inaccurate since the stem

and petiole are completely different. The

stem is at the base of the specimen and is the main trunk from which

the petioles arise from stem's nodes. Along the stems are

the nodes and the segment of the stem between two nodes is known as an

internode. The internodes of Anthurium watermaliense are short. The stem

supports the petioles and thus the leaf blades as well as stores

food, water and nutrients for the plant and carries the water and nutrients to the petioles

and thus to the blades. The

cataphylls, which are the bract-like modified leaves that surrounds any

newly emerging leaf blade, are canaliculate (possessing a channel along the axis). Once dried, the

cataphylls remain as a fibrous material somewhat similar to that on a

coconut husk (see photo, left).

Despite

a tendency for collectors to call a petiole "the stem",

that is scientifically inaccurate since the stem

and petiole are completely different. The

stem is at the base of the specimen and is the main trunk from which

the petioles arise from stem's nodes. Along the stems are

the nodes and the segment of the stem between two nodes is known as an

internode. The internodes of Anthurium watermaliense are short. The stem

supports the petioles and thus the leaf blades as well as stores

food, water and nutrients for the plant and carries the water and nutrients to the petioles

and thus to the blades. The

cataphylls, which are the bract-like modified leaves that surrounds any

newly emerging leaf blade, are canaliculate (possessing a channel along the axis). Once dried, the

cataphylls remain as a fibrous material somewhat similar to that on a

coconut husk (see photo, left).

Our specimen was acquired from

the Arenal Botanical Garden in Costa Rica as a very tiny seedling in the summer of

2005. Since A. watermaliense is a terrestrial aroid found growing in the soil, a

specimen should be given well draining soil and kept slightly damp

most of the year.

Our specimen was acquired from

the Arenal Botanical Garden in Costa Rica as a very tiny seedling in the summer of

2005. Since A. watermaliense is a terrestrial aroid found growing in the soil, a

specimen should be given well draining soil and kept slightly damp

most of the year.

Anthurium species are

known to be highly variable and not every leaf or inflorescence of every specimen

of Anthurium watermaliense will always appear the same. This link explains natural variation and

morphogenesis within aroids and other plant species in non-technical

language .

Natural variation

If you are seeking information on other rare species, click on "Aroids and other genera in the Collection" at the top and look for the